RATTLER RESCUE

And Other Close Encounters the Wilds of Manhattan

Exploring the mountains in search of new plant species, Philadelphia naturalist John Bartram traveled to the Catskills in 1753, visiting the highlands above Kaaterskill Clove, and today’s North-South Lake. His fourteen-year-old son Billy had demonstrated a passion for drawing. Attracted to a large tree fungus known botanically as Auricularia auricula-judae (Jew’s Ear), the boy was about to test the mushroom with his foot when his father pulled him back, away from a rattlesnake coiled beneath it. Despite pleas for mercy from both father and son, their rustic guide slew the creature. Following in the footsteps of his father two decades later, William Bartram toured the southern colonies gathering specimens. The indigenous people he encountered nicknamed him Puc-Puggy (flower collector). While visiting Seminoles, Bartram recounted their camp being invaded by a large rattlesnake.

“. . . the women and children collected together at a distance in affright and trepidation, whilst the dreaded and revered serpent leisurely traversed their camp, visiting the fireplaces from one to another, picking up fragments of their provisions and licking their platters. The men gathered around me, exciting me to remove him; being armed with a lightwood knot, I approached the reptile, who instantly collected himself in a vast coil (their attitude of defence); I cast my missile weapon at him, which, luckily taking his head, despatched him instantly, and laid him trembling at my feet.”

The Seminoles were both impressed and alarmed by Bartram’s feat. They implored him to submit to a scratch, as a blood-offering to the spirit of the slain animal.

“These people never kill the rattlesnake or any other serpent, saying if they do so, the spirit of the killed snake will excite or influence his living kindred or relatives to revenge the injury or violence done to him when alive. . .”

In his 1791 book, Travels through North and South Carolina, Georgia, East and West Florida, Bartram waxed rhapsodic about the virtues of the noble Crotalus. Bartram and some friends embarked on a fowling expedition to the Sea Isles of Georgia. Rising early one morning, Bartram discovered a large rattlesnake, coiled beside their well-trodden path.

“I started back out of his reach, where I stood to view him: he lay quiet whilst I surveyed him, appearing no way surprised or disturbed, but kept his half-shut eyes fixed on me. My imagination and spirits were in a tumult, almost equally divided betwixt thanksgiving to the supreme Creator and preserver, and the dignified nature of the generous though terrible creature, who had suffered us all to pass many times by him during the night, without injuring us in the least, although we must have touched him. . .”

Returning to camp, Bartram shared the discovery with his companions, who were. . . “beyond expression, surprised and terrified at the sight of the animal. . . I am proud to assert, that all of us, except one person, agreed to let him lie undisturbed, and that person at length was prevailed upon to suffer him to escape.”

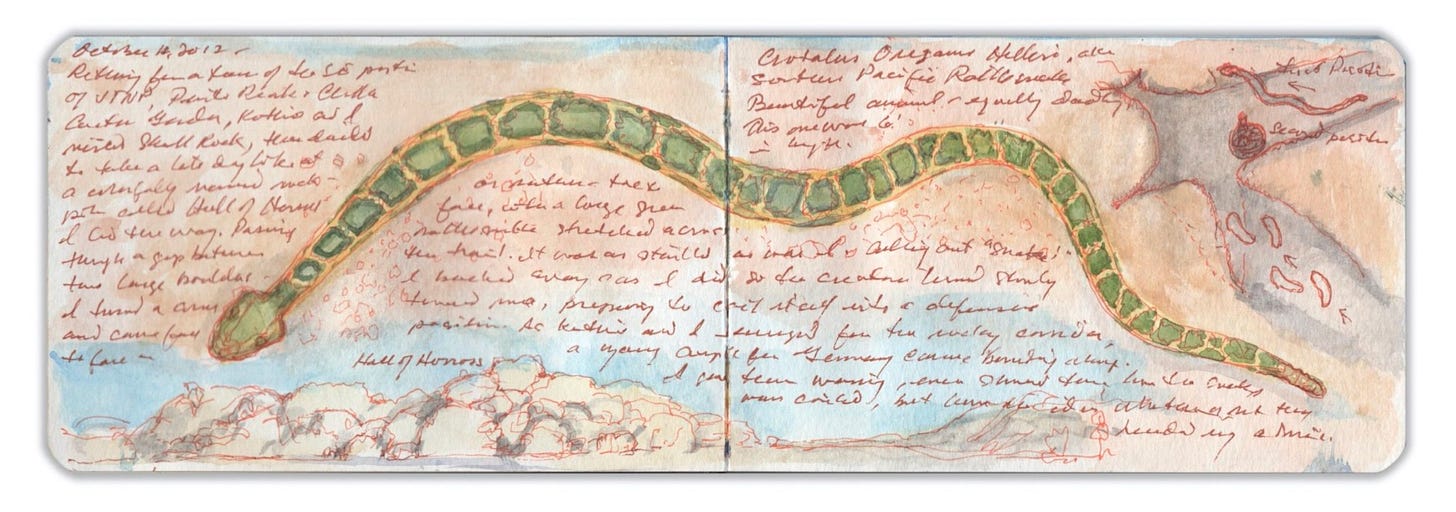

My own wilderness encounters with these fascinating creatures have been few. It has been my good fortune to have seen them first, and not the other way around. Wary of their safety, and ready to defend themselves, none I saw exhibited aggressive behavior. During a visit to Joshua Tree National Park, I was surprised to find a six-foot-long Southern Pacific Rattlesnake (Crotalus oreganus helleri), stretched across the trail. I backed away, leaving it in peace. I reported the sighting to one of the park rangers, who shrugged and speculated that it was probably hoping for one last meal, before bedding down for the winter in his den. While snakebites are rare among two-legged visitors, dogs running off the leash are less lucky. Struck by the beauty of its form, and its green-and-yellow markings, I felt privileged by the encounter. Two dangerous creatures met as strangers, and parted amicably.

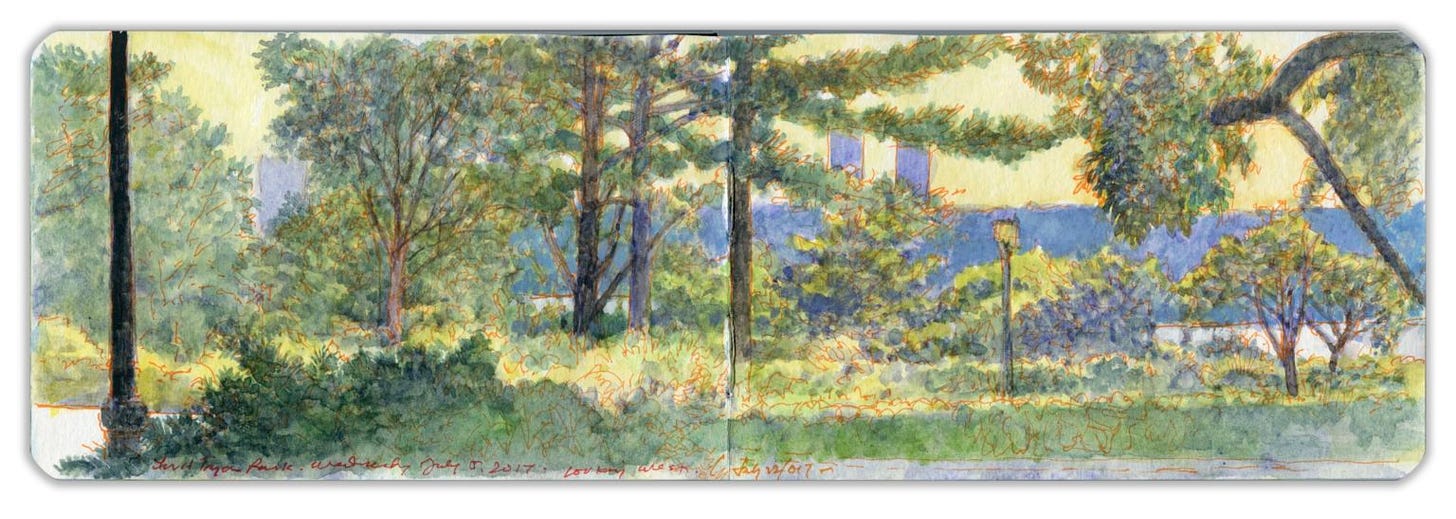

Northern Manhattan possesses nearly five hundred acres of parklands, divided primarily between Highbridge Park, Fort Tryon Park, and Inwood Hill Park, along with smaller parks and green spaces scattered across the island above 155th Street. Since the 1970s nonprofit conservancies have played a key role in locating non-government funding for the maintenance and improvement of New York parklands. The New York Restoration Project planted one million trees, making New York one of the greenest cities in the nation. The Heather Garden and Alpine Garden in Fort Tryon Park attract thousands of visitors every year.

Working on a painting of the Heather Garden one hot summer day, Kathie sat beside me, reading a book. Crying out in alarm, she pointed to a small snake writhing in agony on the hot asphalt, warmed by a burning sun. I rushed over, lifted it carefully with the end of my brush, and laid it under a bush. Sprinkling the creature with cool water, I studied its form, the shape of its tiny head, narrow neck, taupe coloring, the paired markings running down either side of its spine. “What are you?” I wondered. And suddenly, I had the answer. It was a timber rattlesnake—Crotalus Horridus. These creatures are not hatched from eggs but born live, a dozen at a time. “Where’s your mother?” I pondered. “Where’s the rest of your family?” Revived, the little serpent flicked its tongue and disappeared into a stone wall at the garden’s edge. I hoped that Billy Bartram and his Seminole hosts would have approved.

Some time later, as Kathie and I were walking home from The Cloisters, I noticed a noisy cluster of Spanish-speaking kids gathered beside the stone wall on the northern perimeter of Margaret Corbin Circle. One of them was probing the stones with a long twig. I drifted over to investigate the commotion. The boy turned to me with a cocky grin. Perhaps he was proud to show his friends something wild he could torment. Hiding in the cracks between the blocks where some mortar had been lost I could see the head of a small snake.

“Dejalo,” I cautioned him, “Esa serpiente es MUY peligroso. Es un cascabel.”

Witnessing this exchange, a woman—presumably one of their mothers—hastened them all away. The boy who had discovered the snake clung to his twig, before tossing it aside when he boarded the bus.

It is hard to imagine that today’s coastal forest, which stretches from the Gulf of Mexico into Canada, covered a far greater area than the 18th-century woodlands the Bartrams had known. The revenant forest of the late twentieth century restored the habitat of long-absent predators such as bear, wild cats, coyotes, and even wolves. The number of White-Tail Deer has gone off the charts. Species seldom seen in settled areas became commonplace once again. Apart from the ubiquitous rock doves and tree-squirrels, our Manhattan neighborhood is home to osprey, bald eagles, skunk, raccoon, woodchucks, and countless species of songbirds. Walking through The Ramble in Central Park, I noticed a wild turkey-hen forage in a clearing. On a nearby bench sat a homeless man, with his worldly possessions piled beside him. His eyes were fixed on the bird, as it pecked at the ground. Seeing me approach, he called out. “Hey mister. What’s that bird?”

“A female turkey,” I replied. He looked relieved.

“Thanks! I knew it weren’t no pigeon.”

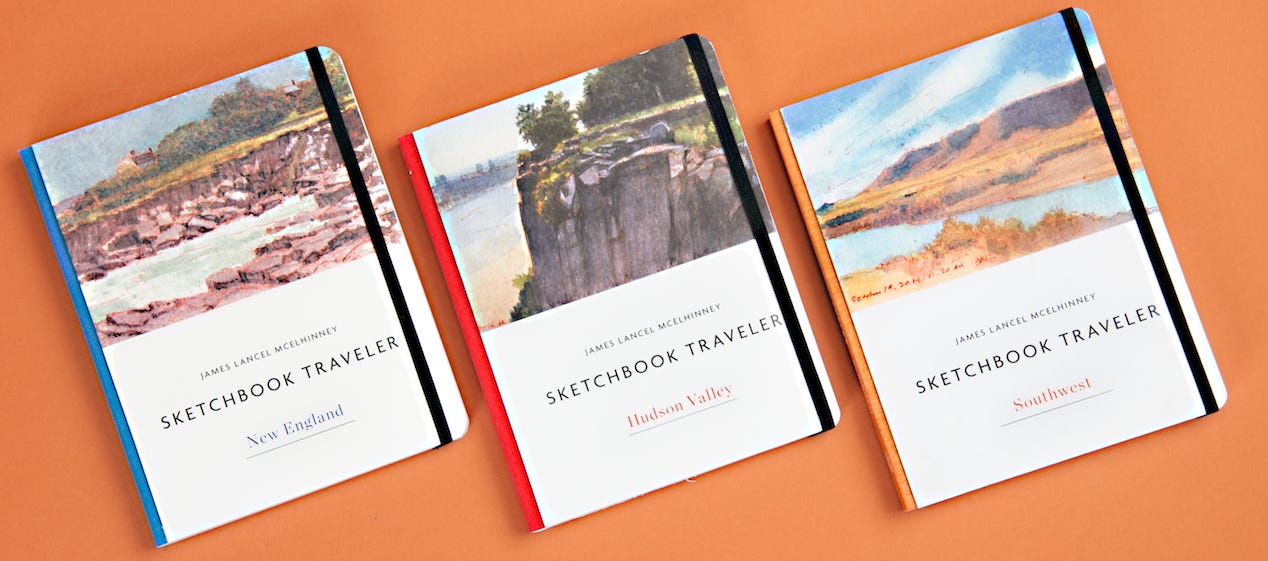

THANKS FOR READING! If you enjoyed this post, please subscribe by clicking on the button above. Read about more True Places by adding the Sketchbook Traveler series to your library. Just released by Schiffer Publishing: Sketchbook Traveler New England. PREVIEW.

SPECIAL OFFER: All three books foir $45 USD exclusively from ecoartspace.org. Click on the image below to place your order. LINK