Springtime is so magical in the Adirondacks that one could easily blink and miss it. The hilly coast of Lake Champlain is blessed with a sparsity of black flies (British midges) that swarm in the High Peaks and upcountry waterways. Snowmelt forms vernal ponds that breed mosquitoes. The silver lining is that bats and birds feast on these airborne vexations. I am continuously amazed at the finches, woodpeckers, mourning doves, and robins that survive through our subzero winters. Flocks of Canada geese, Baltimore Orioles, Vireos, and Carolina Wrens herald the arrival of spring. Kathie and I ventured onto our porch, on the year’s first warm evening. The gently sloping roof is supported by three columns topped by Doric-style capitals. A small squarish ledge was formed by one corner of each facing inward. Kathie noticed a telltale pile of dried stems and grass, as we sipped our pre-prandial cocktails. The pile grew larger, day after day. A feathery blur sped past my head one day, and dived into the nearby foliage. The Robin clung to an Azalea branch, crying “Eek-eek. Cuck-cuck-cuck.” I followed her flight path, as she flew to the highest branch of a gnarled apple tree, then onto the gravel driveway, to a stump at the edge of our lawn. Each leg of the journey brought her closer to the house.

One evening we realized there were two Robins, not one. They worked in relays to scavenge materials to build the nest. Their sharp beaks had ripped open a loveseat pillow for its fluffy mock-goose-down stuffing. We beheld their progress from behind our kitchen window. The Robins returned our gaze, but without much alarm. Each took turns, building and foraging. The female backed into the hollow once the nest was complete, to lay a clutch of eggs. She would greeted us with raucous rebukes, whenever we came or went. Her mate flew dive-bombing sorties, attempting to drive us away. His wingtip once grazed my head. These defensive maneuvers intensified after the chicks had hatched. I knew from personal experience these creatures meant business.

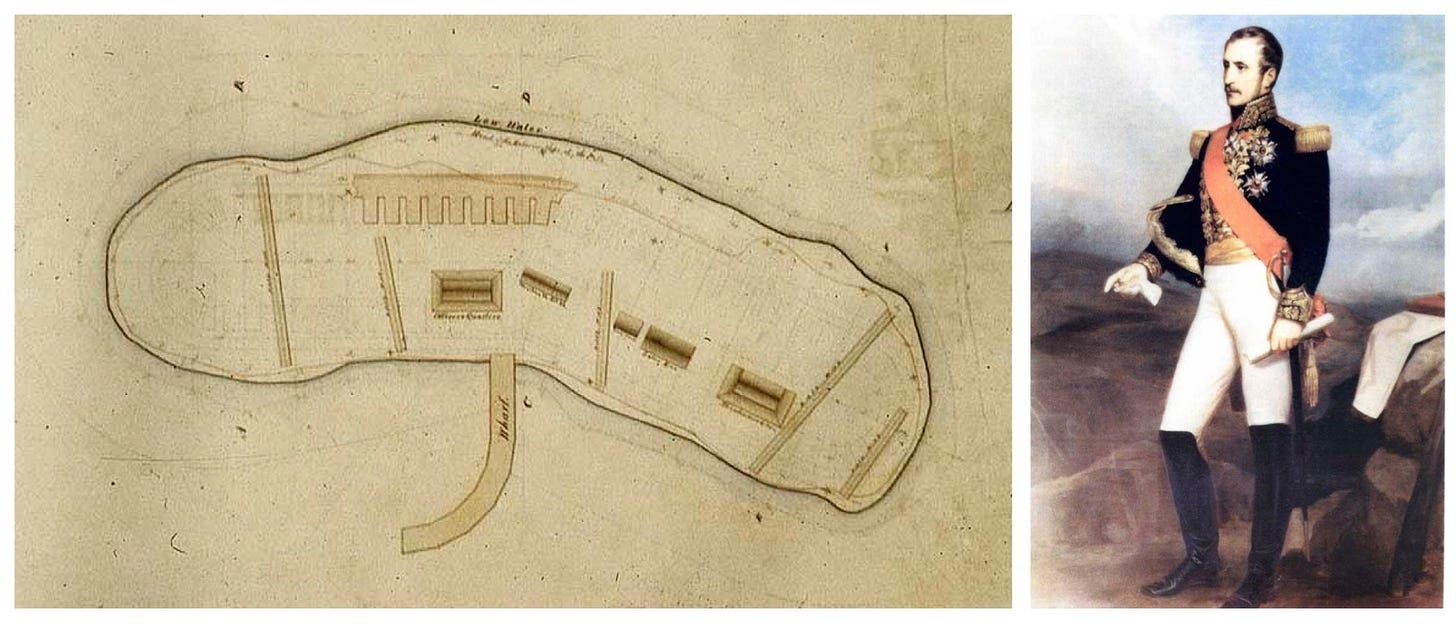

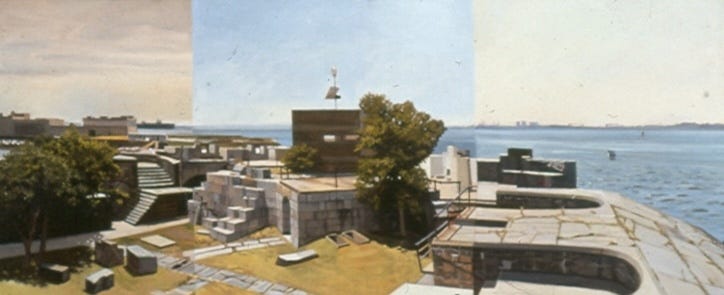

Simon Bernard was a French military engineer and Napoleon’s Aide-de-Camp, whom Congress made brigadier general the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in 1816. Fact tracking Bernard from the Grande Armée’s defeat at Waterloo to high rank in the American military presaged the use of Von Braun’s Peenemünde rocket scientists in the formation of NASA. Bernard oversaw the design and construction of Fortress Monroe on Old Point Comfort and planned a three-tiered island battery to be guard the outflow of the James River into Chesapeake Bay. Boatloads of rubble were dumped on a shoal near Old Point Comfort. Construction on the fort began when the artificial island had risen to six feet above the high tide. Work progressed slowly. Robert E. Lee was assigned to the project during the 1830s. The army scaled back its plans when gaps appeared in the granite masonry, which threatened to sink the islet. Fort Wool saw action only once—during the Battle of the Ironclads in 1862. It served as an active post until it was decommissioned in 1953. Ripraps Island is now tethered to the south entrance to the Hampton Roads Bridge Tunnel by a narrow causeway. I produced five or six paintings of Fort Wool, one of which hung beside Edouard Manet’s painting The Battle of the Kearsarge and the Alabama, in an exhibition at Norfolk’s Chrysler Museum in 1998.

There were only two ways to get onto the island in 1992. Harbor tours departing from the Hampton waterfront delivered visitors to the island several times each day. Wrangling wet paintings on and off a boatload of tourists was not an appealing prospect. I explained my predicament to Hampton city historian Mike Cobb, who cleared me to park in a lot behind the Virginia Department of Transportation maintenance complex, at the south tunnel entrance off Interstate 64. Making a sharp left-hand turn into from a four-lane highway was almost as hair-raising as merging into the northbound traffic that seldom observed speed limits. The fort itself was situated on the far side of a littoral margin of tall grasses was traversed by a muddy track that led to a rickety chain of catwalk gratings laid across a rocky causeway. Mike had cautioned me about seabirds, but not the rookery that stood between the parking-area and the causeway. Screeching terns attacked as I started down the path. Shielding my head with a paintbox, I imagined Stukas wailing over Dunkirk, or Tippi Hedren running for her life in Alfred Hitchcock’s film The Birds. Running this gauntlet day after day became a running gag—like the motorcyclists in Fellini’s Amarcord and Bill Forsyth’s Local Hero. If Dixie sea-fowl had no sense of humor, North Country Robins have even less.

The female Robin enfolded the nest in her wings, to shelter unhatched eggs. Security protocols intensified, but not so daunting as the Rip Raps squadrons. Tiny heads appeared in the nest one morning. The hatchlings trembled and squeaked. Their parents took turns stuffing grub into the chicks’ upturned beaks. The featherless newborns seemed to grow larger by the hour. Within a few days, they were covered in plumage. Tensions between the youngsters revealed each with unique personalities. We saw less of the adult male as time went on, while the exhausted mother was losing her patience. One morning the nest was empty. The Robins returned to lay another clutch, as spring gave way to summer. Summer faded into autumn. The onset of winter was mild, but January brought heavy snowfall that persisted into March. Strands of windblown thatch clung to the nest through the winter.

The nest stood abandoned the following year. Its modest hollow had become a crucible of miracles when it brought forth new life. Watching it now fall to ruin was doleful, even elegiac. Housepainters received strict instructions to leave the nest alone. Call me sentimental, but we had come to regard our Robins as guests—even neighbors. Winter came and went once more. A length of thatch still swung in the breeze like a gibbeted buccaneer, or perhaps an omen of hope.

White floral clusters burst into bloom on a nearby Azalea, announcing the advent of spring. Green shoots pushed up through the turf, followed by daffodils. Stepping out of the house I noticed the pendulous lump was gone. It had neither fallen on the floor, nor been blown onto the lawn. The nest suddenly looked almost tidy. Could it be? And then I heard, “Eek-eek-eek, cuck-cuck-cuck” The Robins had returned.

—James Lancel McElhinney © May 30, 2025

Thanks for your support! If you are enjoying these articles, please let your friends know how they can join the conversation by sharing this LINK

NB: All images published herein are reproduced under Fair Use, etc.