Hans-Christian was one member of the group who spoke very good English. He was keen to learn more about Eliza, not only because of her daughter's close friendship with Sisley, but also because of her role in promoting plein-air etching. Kathie explained that Eliza had an apartment in Paris, near Jardins de Luxembourg, from which she made sketching excursions to places like Cernay-la-Ville, and Chevreuse; either of which today would be a ninety-minute drive from Moret. Christian and his colleagues were thrilled to add yet another name to Moret’s roster of artists along the Route des Impressionismes—a European Union heritage-tourism initiative that links numerous sites across thirteen countries, from Greece to Greenland. We learn that Moret has recently established an artist residency as a cultural exchange, with the Peoples’ Republic of China. One day a painter from Sichuan arrived on the banks of the Loing, and one thing led to another

We had places to go, and our hosts had roles to play in the annual European Heritage festival that Moret would kick off on Friday. Following an exchange of cartes-de-visites, we all posed for a photo at the foot of the Sisley monument. We had planned to visit the graves of Eliza and her daughters before our departure. We instead accepted an invitation to tour an exhibition of local artists, which left barely enough time to catch the Paris train. Upon our arrival at Gare de Lyon, we discovered that some minor greffière at Centre Georges Pompidou had just cancelled our hotel reservations. This was clearly just an administrative blunder, but Kathie and other speakers traveling to the symposium suddenly found themselves with nowhere to stay. Calls to the Pompidou Center were met with indifferent domages, but Kathie’s contact at Musée d’Orsay was more helpful. We were found a room at Hotel Exquis, not far from Place de la Bastille, at 71 Rue de Charonne in the 11eme Arrondissement. We were welcomed to the boutique hotel by a lovely young woman, who showed us to our room on the uppermost floor. Three of us could barely fit into the lift, and our bags were ferried up separately. Every interior surface of the hotel was embellished with floral designs and other artistic patterns, which added to the festive ambience. The room was small, but its bathroom was commodious. The bed was large, with barely enough room to circumnavigate its margins. A single window opened onto the street, and Parisian rooftops.

We dined at La Belle Équipe, a popular bistro at the corner of Charonne and Rue Faidherbe. Our repas was consumed in a fog of second-hand cigarette smoke. We reviewed our trip to Moret, which mostly had been a success. Our only regret was not having visited the cemetery to pay our respects, so I floated an idea. Kathie would be busy for two days, as both a presenter and attendee of the Faire/Oeuvre symposium at Musée d’Orsay. I could return to Moret on my own, to tie up loose ends, visit the cemetery, and take some more photos. Unfortunately, the chest cold I had been nursing since we left New York laid me low the next morning. After breakfast, Kathie took an Uber to the museum. I climbed into the tiny lift and returned to our room. The day was warm, so I opened the window and lay down to rest, only to be awakened by a trumpet serenade. It may be that “Never on Sunday” was the busker’s favorite melody, or perhaps he was Greek, but all day long he played no other tunes. By evening my condition had improved, but Kathie nixed a return to Moret. We were in Paris. There was much to do, apart from the symposium.

The following day I was on the mend. After a delightful petit-dejeuner, served a la buffet in the lower salon of Hotel Exquis, we wandered over to Place de la Bastille, then through the gardens along Canal St.-Martin. We paused for lunch at an Italian trattoria at the head of Quai Henri IV. Young people sped past us on electric skateboards. These were not sporty youths wearing kneepads and backward ball-caps, but business-casual daredevils, jousting with hard-metal motorists. We afterwards walked along the river, crossed the Pont de Sully, and wandered down Rue St.Louis en l’Isle. Tourists queued up for creme-glace at Berthillon, as usual. Crossing Pont St. Louis, we beheld the doleful sight of Notre Dame cathedral, rising up behind a daunting barrier capped with razor wire. A warning that the site is under video surveillance is sandwiched between the names and logos of construction firms conducting the repairs. On April 15, 2019, just five months prior to our visit, a fire swept through the cathedral’s attic, destroying most of the lead-clad roof and consuming the 19th-century flèche, or spire. Intense heat generated by the blaze, which burned for fifteen hours, was absorbed by the medieval masonry. When engineers reckoned that the stonework might have sustained sufficient damage to comprise structural integrity, its flying buttresses and cathedral walls were shored up with massive timbers—pinioning the building Gulliver-like within a wooden cage. My first visit to Paris coincided with Whitsuntide, or Pentecost—when a rushing wind and tongues of fire filled the Apostles of Christ with the Holy Spirit. Mass was underway in the cathedral. I was standing beside the statue of Charlemagne when a wave of sound broke over me like a tsunami. My bones vibrated like tuning-forks, leaving me breathless. It happened again, and I wept. The great bourdon tolled again and again, filling me with wonder, awe, and strength. This sonic epiphany emanated from Emmanuel—the largest of Notre Dame’s bells, which was cast in 1686, and given the name “God is with us.” It was seldom rung, except on the highest of Catholic holy days, until the voice of God welcomed Allied forces to Paris on Friday August 25, 1944—an event recreated in the closing scenes of René Clément’s 1966 film “Is Paris Burning?”

Kathie and I drifted through the Latin Quarter, drank a few beers at Le Mazarin on Rue Jacques Callot, a few doors down from Galerie Xavier Eeckhout, which previously had been occupied by Galerie Darthea Speyer, and paid our respects at the former Hotel Alsace, where Oscar Wilde had lost a duel to the death with his wallpaper. We lit a few candles at l’Eglise de Saint-Germain-des-Prés. Kathie had recently lost her parents several years prior, and my mother had passed away less than a week before Notre Dame went up in flames. A beloved friend who later would die, was then battling Leukemia. Both Anne and my mother cherished a deep and abiding faith. A few weeks later I called on Father Sebastian at El Sanctuario de Chimayo, to arrange for masses to be dedicated to my late mother and ailing friend. I felt sure they would have appreciated the modest gesture.

As I jotted down journal entries on our return flight to New York, my thoughts went back to Moret, and our uncanny good to have met Anne and Gilles, the staff at the Hotel de Ville, kindly strangers, and elderly Moretains. I hoped that by visiting Moret, we had done more than satisfy our own curiosity. Kathie was tying up loose ends; finishing the manuscript of Restless Enterprise: The Life and Art of Eliza Pratt Greatorex for the University of California Press, which released the book one year later, at the height of the pandemic. I would like to think that by stalking ramparts, stocking up on barley suckers, and communing with spirits, we brought more than visitor revenue to the community. Like Paige McClanahan’s New Tourist, we carried in and we carried out, but we also left a trace. Light had been shed on a small part of local history that was little-known to the Moretains—even to Les Amis de Sisley and Les Amis de Moret. It would be arrogant to say that Moret was somehow improved by our visit, but as the train sped through Fontainebleau Forest on its way to Gare de Lyon, I was suddenly ambushed by a sense of loss. Whatever we had left behind, we hoped it was something of value.

POSTSCRIPT

Eliza Greatorex passed away on February 8, 1897. The paper trail shows that her remains were placed in a coffin, and removed from her in-town apartment near Luxembourg Gardens. It was then delivered to Gare de Lyon; presumably for transport to Moret. After that, the trail went cold. This was typical of the peripatetic Eliza, even in death. Both her father and sister are buried in Brooklyn’s Green Wood Cemetery. Neither grave is marked in any way. We only located the graves by tracking down plot-numbers recorded on a map, and were shocked to find Reverend Pratt and his housekeeper stacked in the same grave. Perhaps this lackadaisical approach to thanatotic sentimentality is an Irish trait. The protestant graveyard outside of Eliza’s Donegal hometown is a grassy patch of lumpy turf, enclosed within crumbling walls. Moldering headstones stagger to and fro, like bibulous revelers. We failed to find her mother’s grave. Crisply carved inscriptions had long ago surrendered to the melting embrace of twenty-nine thousand fine soft days. We didn't linger, chary of a misplaced step that might break through a worm-eaten coffin, and trample long-forgotten bones.

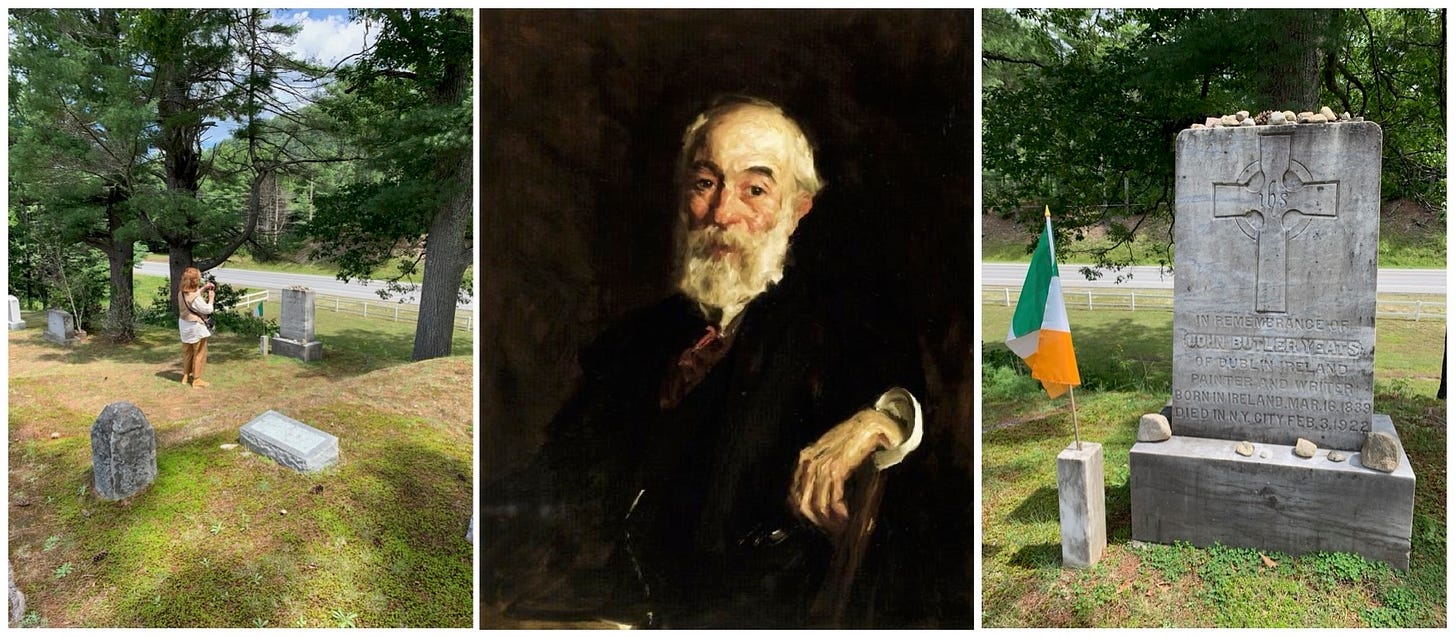

Ulster-born poet and painter John Butler Yeats passed away on February 3, 1922. He had resided for 15 years at les sœur Petipas’s boarding house, at 317 West 29th Street in Manhattan’s Tenderloin district. With no family nearby to claim his mortal remains, Yeat’s friend and protégé Jeanne Robert Foster (née Julia Elizabeth Oliver; 1879-1970) shipped the body to Chestertown, New York. There it was buried in a section of the Oliver family plot. Yeats’s famous children declared their firm resolve, to return their beloved father to Ireland, but they never got around to it. Kathie and I paid a visit to Yeats on Saint Patrick’s Day 2021. We spilled a dram of Jameson’s on his grave, set a few stones on the headstone, and raised a glass to his memory.

A few weeks after we paid our respects to Yeats, I received an email with photo attachments from Les Amis de Moret president Hans-Christian. He had recently located Eliza Greatorex’s grave in the municipal cemetery, and was struck by its unusual configuration. The women are buried side-by-side, in such a way that three graves might be mistaken for one. Alfred Sisley was very much alive when Eliza passed away, and would have attended her funeral. When he succumbed to throat cancer two years later, the Greatorex sisters interred Sisley’s remains in one of the graves reserved for them, marking his final resting-place with a large stone and a sprig of juniper that today is a fully-grown tree. This left only two gravesites to be shared by three women. Today they lie entombed beneath treble-tiered limestone slabs. Eliza’s stone is flanked on either side by Eleanor and Kathleen—as inseparable in death as they had been in life. Kathleen's stone is blank, but Eliza’s bears a long memorial to her parents, her beloved husband, and her brilliant son Thomas, whose senseless murder in Durango, Colorado had broken his aged mother’s heart. The inscription concludes with a verse from the Gospel of John.

"GOD IS LIGHT AND IN HIM IS NO DARKNESS AT ALL"

(The End)

—James Lancel McElhinney © 2024

READ Katherine Manthorne’s biography of Eliza Greatorex, published by University of California Press: CLICK here