I knew very little about Latin American art in 1990. Like most norteamericanos, I was familiar with the Mexican muralists, Chicano and Spanish colonial art, and some Caribbean artists. Puerto Rican-born Rafael Ferrer was prominent figure in the Philadelphia art scene, allied with a group of conceptualists that included Italo Scanga, Bill Beckley, and Harry Anderson. Celebrated Old Colony native Pablo Delano was a freshman at Tyler when I began my junior year. My first adventure in matrimony was with a Tyler alumna, whose great-uncle had helped to create Mexico City’s famed Teatro de los Insurgentes. Hayden Herrera’s biography of Frida Kahlo in 1983 inspired a younger generation of feminists, while the 1986 Diego Rivera retrospective at the Philadelphia Museum of Art buoyed proponents of representational painting.

South American artists such as Armando Reverón, Tarsila do Amaral, Helio Oiticica, and Lygia Clark were mostly off the radar, but thanks to the advocacy of Patricia Phelps de Cisneros their works now abide at MoMA. Oswald de Andrade’s 1928 Manifesto Antropófago proposed that post-colonial Brazilian artists could resist European cultural domination by cannibalizing their former colonizers. Had I known of Andrade in 1990, the project I was about to launch might have been easier to articulate.

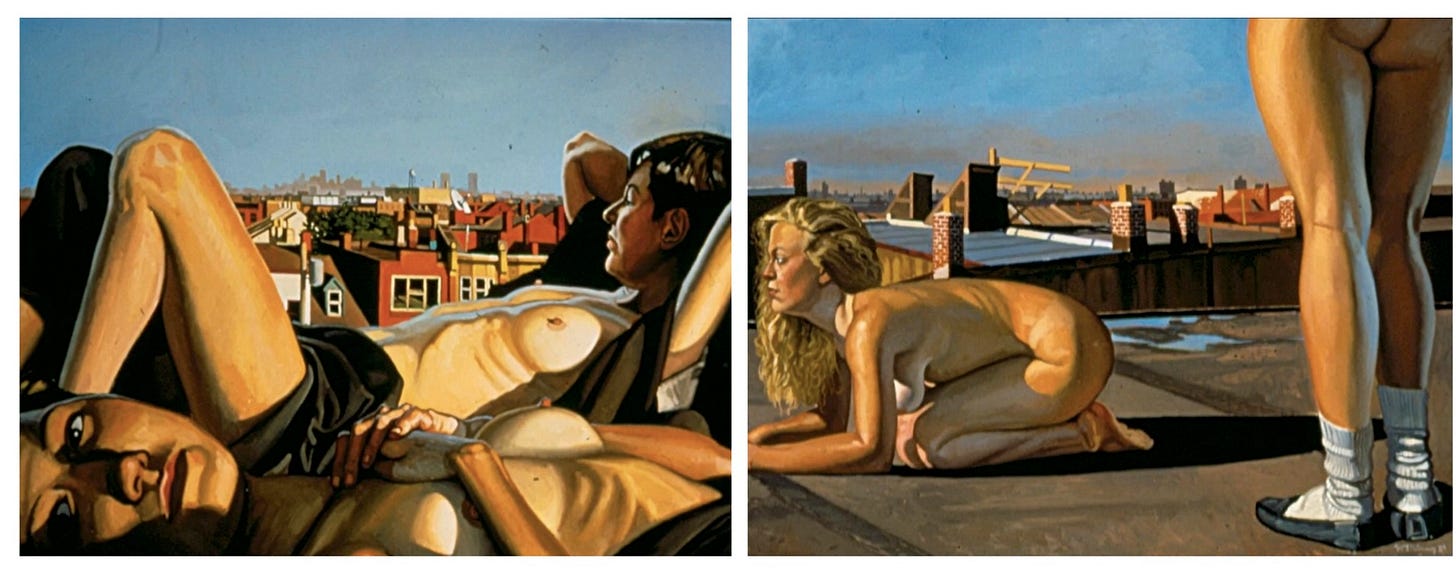

My paintings of female nudes during the 1980s caught drew flak from stay-in-your-lane forerunners of today’s cancel-culture. Their argument was that the male gaze in any form was an insult to feminine dignity. Previous blogposts have discussed my Portrayals project at some length—how female models art-directed self-portraits-by-proxy—reenacting art-historical poses from works by male artists, to cannibalize the male gaze. To quote Exposure Therapy and Don’t Delete Art founder Emma Shapiro, viewers were invited “. . . to investigate the roles of autonomy and participation in nude portraiture.” Conventionally attractive sitters decolonized their own female bodies, sometimes with a measure of humor.

Nicole Iverson worked in my life drawing class at a southern university in 1995. Raised in the suburbs of New York City, Nicole was acclimated to a far more diverse demographic than what she found in Old Dixie. The university was quite different than its semi-rural surroundings. For example, the art school faculty included a Korean, a Palestinian Christian, a South Asian, and the Afghan imam of the local mosque. While a small Muslim community had grown up around a local rug mill, the surrounding region was predominantly Baptist, Evangelical, and white. There was also a sizable African-American community, but social interactions across the racial divide seldom seemed to occur off campus. Nicole’s Mediterranean roots were evident in her thick black hair and bronze complexion.

“Growing up outside in the Metro New York area and then going to college in the south, I had just never seen only black and white and no other shades of anything. People in Greenville would ask me, ‘What kind of Mexican are you? What kind of Indian are you?’ And I'm like—"The kind that eats ravioli? I don't know if you've ever heard of us . . . I just felt so completely out of place. I'd ask them, ‘What's your background, what's your ethnicity?’ and they would say ‘I'm a white American’. And I'm like, ‘That’s a cheese. That’s not an ethnicity.’ They just didn't grasp it at all. It was interesting. When I was a kid, I once got called an ethnic slur, but nobody I knew did that because there’s a derogatory term for everyone . . . like in Spike Lee’s ‘Do the Right Thing,’ . . that moment where Mookie and Sal at the end of the day . . . it's just like, hey, we could all say this about each other . . . that's the beauty of New York—everybody just leaves each other alone.”

Nicole describes herself as “a deep feminist, raised by deep feminists.” She majored in English in college, with a concentration in ethnic studies. Nicole remembers her mentor fondly.

“It breaks my heart that I can no longer talk to Gay. I still have so many more questions for her. I was taking a course about Black women writers with her, and Bi-gender Look at Jewish Literature and feminist theory. And so there I was in my early 20s—living with a couple of girls out on a farm . . . reading feminist theory and, and feeling really free with my body, to do what I want with it.”

After earning a bachelor’s degree Nicole entered a graduate program in Colorado, and continued to work as a life model at nearby colleges and art schools. As she recalls—

“I worked with a photographer who taught a nude photography class. I hung some photos of me in my bathroom. People would see them and say, ‘Oh . . . you model nude. Isn't that uncomfortable?” And I would say ‘not for me.’ It never has been. I love an all-over tan and prefer to swim in the nude. My favorite beach is at Sandy Hook, New Jersey. It's a nude beach. What am I covering up, and for whom? When society tells me to cover up—it’s sexualizing my body, at a time and a place where I don't feel sexual—so don’t view me as a sexual object.”

Owing to a limited pool of models off campus, the university where I met Nicole hired work-study students as life models in its studio classes. This normalized the practice of posing nude as professional and respectable. My proposal to adopt the same practice at a midwestern university was met with prudish disdain. It was amusing to note that a Bible Belt art school could be more progressive than one of its peer institutions, in a self-styled bastion of liberalism.

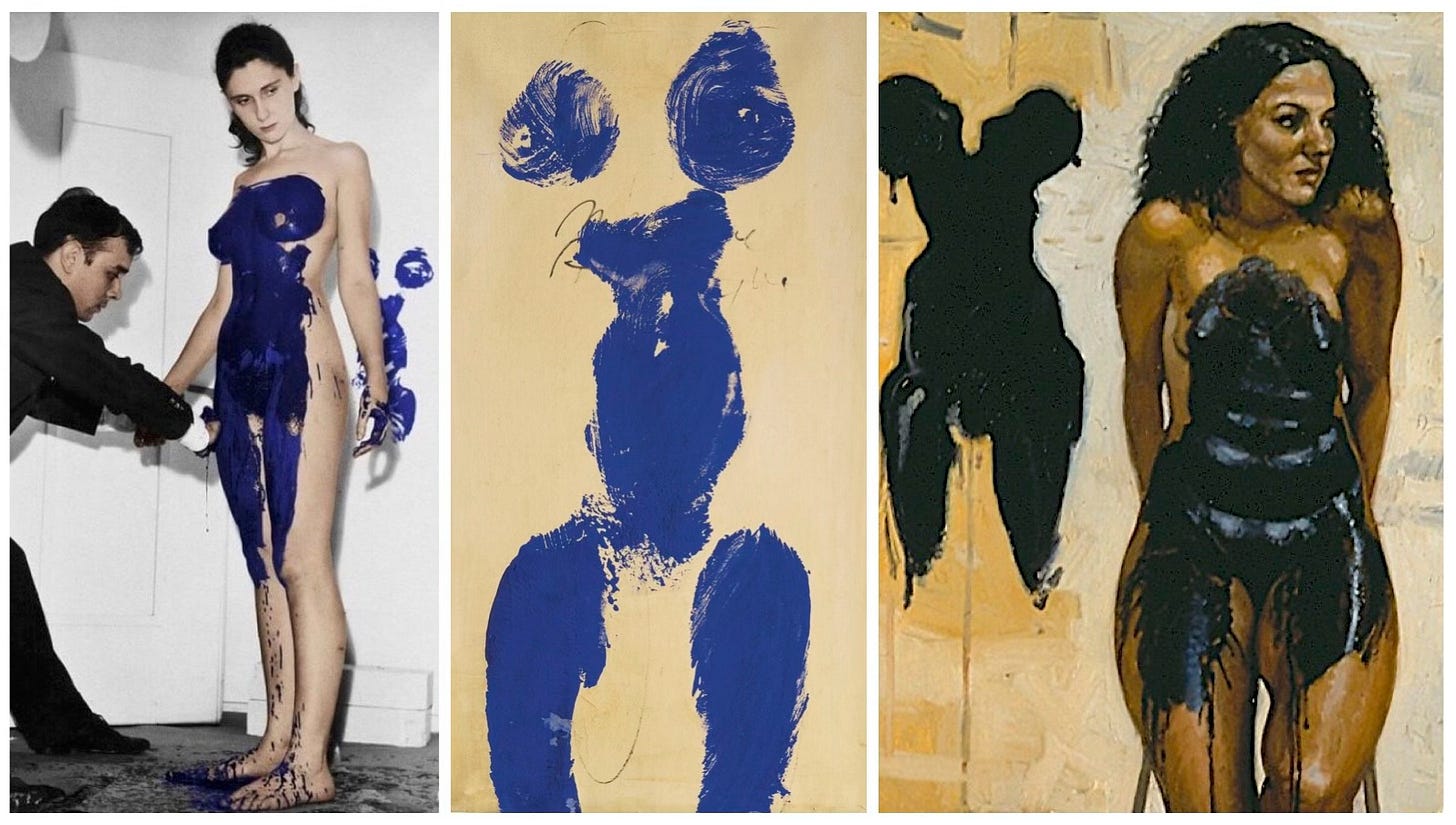

When Nicole agreed to model for me privately. I asked her to select her own pose from the history of art, and explained that we would do our best to recreate it. After a couple of get-acquainted drawing sessions, she decided to reenact an Yves Klein’s Anthropometry, or human brush—from a 1960 performance-piece in which a group of young women slathered themselves in blue paint and pressed their naked bodies against raw canvases. Footage of the event was featured in the 1962 documentary Mondo Cane. Klein was stricken with a heart attack during the film’s premiere, and succumbed a short time later.

Neither Nicole nor I had any experience with body painting, but I recalled a conversation with a sculptor who had collaborated with Philadelphia body-paint pioneers Peanutbutter and Flash. Their concoction was described to me consisted of powdered tempera paint mixed with glycerin, distilled water, and dishwashing liquid. The local art supply store carried plastic jars of pulverized colors. Blue was unavailable, so we settled for black. The combined ingredients yielded a gallon of the inky potage, which I mixed to a milkshake consistency. The liquid was applied to Nicole using sponges. Dregs were dribbled onto her breasts, and gravity did the rest. Perhaps we should have filmed the process, as Jacopetti & company had done with Yves Klein. After Nicole pressed a Rorschach-like impression onto the wall, she posed beside it.

“I remember sitting on the stool and trying to find a comfortable position. Because you were painting in oil, you'd be there a long time. And every time that I've modeled it's always been the same thing. Pick the most comfortable pose you think you can do, and when you sit in the same position for three hours, at some point it's gonna hurt, right? Sooner or later, you need a break . . . and just sitting on the edge of that stool . . . I remember it being uncomfortable after all these years.”

I worked quickly, borrowing Avigdor Arikha’s practice of starting and completing a painting in one session. The 9 x 12-inch panel took no more than three hours to complete. Accepting such temporal constraint made the act of painting more of an event in a pas-de deux with Nicole in her pose. As she recalls:

“I feel more anonymous when I'm modeling, like it's not about me. It's really about channeling the universal humanity within all of us. Trees in the forest don’t judge each other. They don’t say things like ‘Your bark’s too lumpy.’ I really just feel very natural when I’m posing—like a tree. It’s a way of being closer to our natural state. Modeling made me feel closer to the universe, closer to humanity, closer to God—seeing myself as part of the larger picture. It wasn't really about me. How will people judge me, because I posed nude? I really hope that one day the painting would be hanging in a museum, where my kids and grandkids would walk by and say, ‘Oh my God. We're related to her!’ I love the work that I’ve done, and I'd love for it to be seen. And if people aren't into it, well . . . there are plenty of people who’ll approve of me, and plenty who won’t. I’m okay with that.”

—James Lancel McElhinney © 2025

NB: Many thanks to Nicole Iverson for her editorial input on this article.

Thanks for being a free subscriber to True Places. Consider upgrading your subscription to paid, to support this publication.