CREEPING BITES & ACID BATHS

Continuing Adventures in Aquatint Printmaking

The first bites of our aquatints seemed promising. It’s a peculiar term, that might leasd the uninitiated to summon up visions of vipers, vampires and celluloid sharks. In printmaker lingo, a bite is how exposure to acid forms ink-receptacles below the surface of a plate used in intaglio printing. The Italian word intaglio covers a range of subtractive processes used to carve wood, stone or metal. It was also used to describe images created by cutting designs into metal plates—first in the decoration of weapons and armor, and later in the production of prints on paper. Medieval armorers discovered that they could accentuate the contrast between the incisions and the surrounding metal by first applying a patina, and then removing it from surfaces that were brightly polished. This left a residue of the patina deep in the cuts, creating an effect that resembles an ink drawing. Printers soon discovered that by rubbing ink into incised designs made on a flat plate, and then subjecting it to sufficient prerssure, they could transfer its mirror-image onto paper. Copperplate engraving soon replaced woodblock prints, which were far more laborious to produce. Metal plates also allowed engravers to produce more detailed imagery.

Carving with acid began like engraving; as a technique for adorning fine armor with decorative embellishments. The process was adapted to printmaking by armorer Daniel Hopfer (1570-1535) in the free imperial city of Augsburg. Results comparable to engraving were achieved in a fraction of the time required to cut a design by hand. The plate is coated with an acid-resistant ground, through which fine lines are drawn with a steel needle, exposing bare metal. The plate is then be submerged in hydrochloric acid, for whatever length of time is required to achieve the desired results, which also could be governed by adjusting the ratio of water (H₂O) to Ferric Oxide (Fe₂O₃). A longer bath, or stronger acid, will yield a deeper the bite. The deeper the bite, the darker the line.

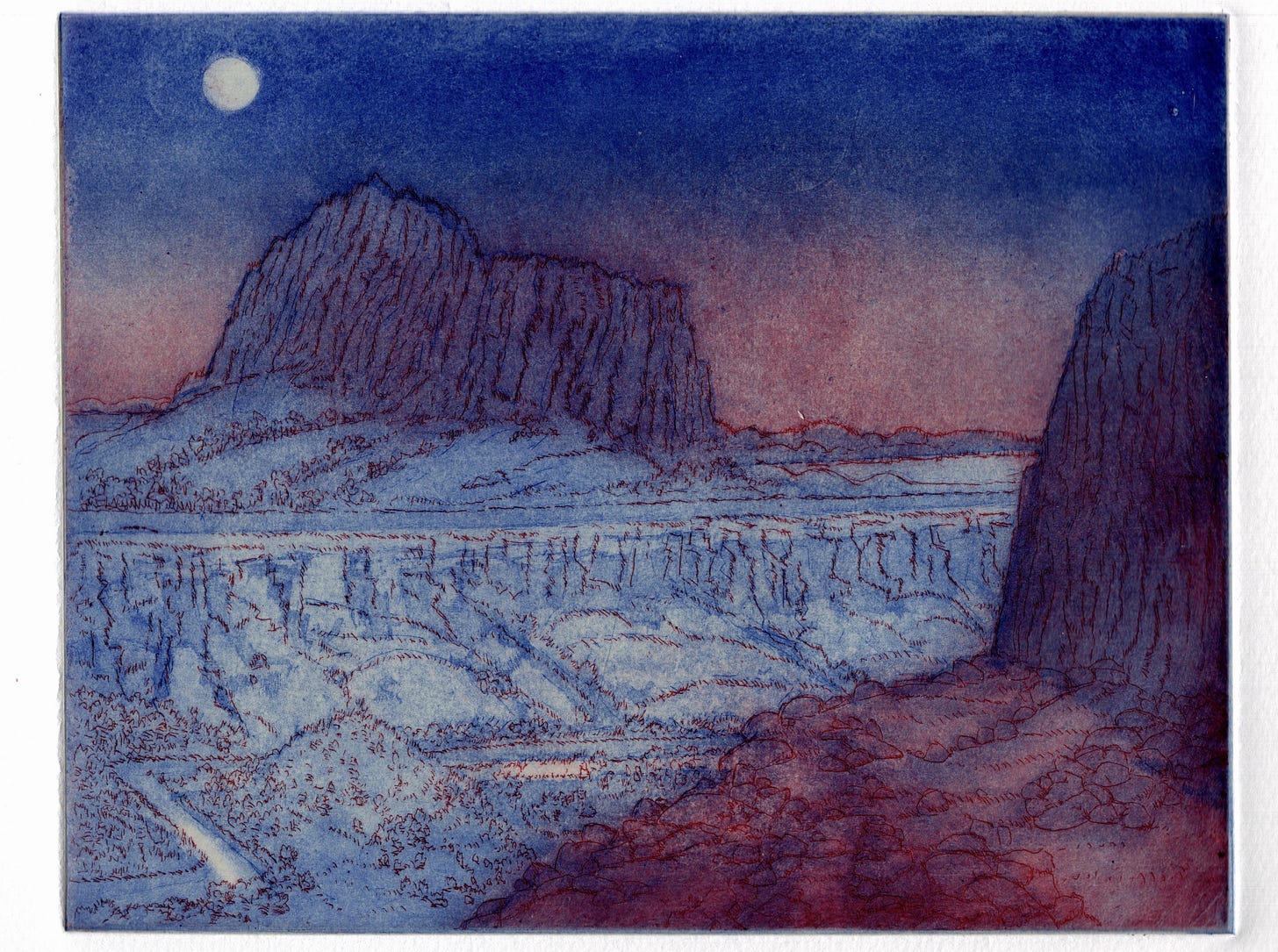

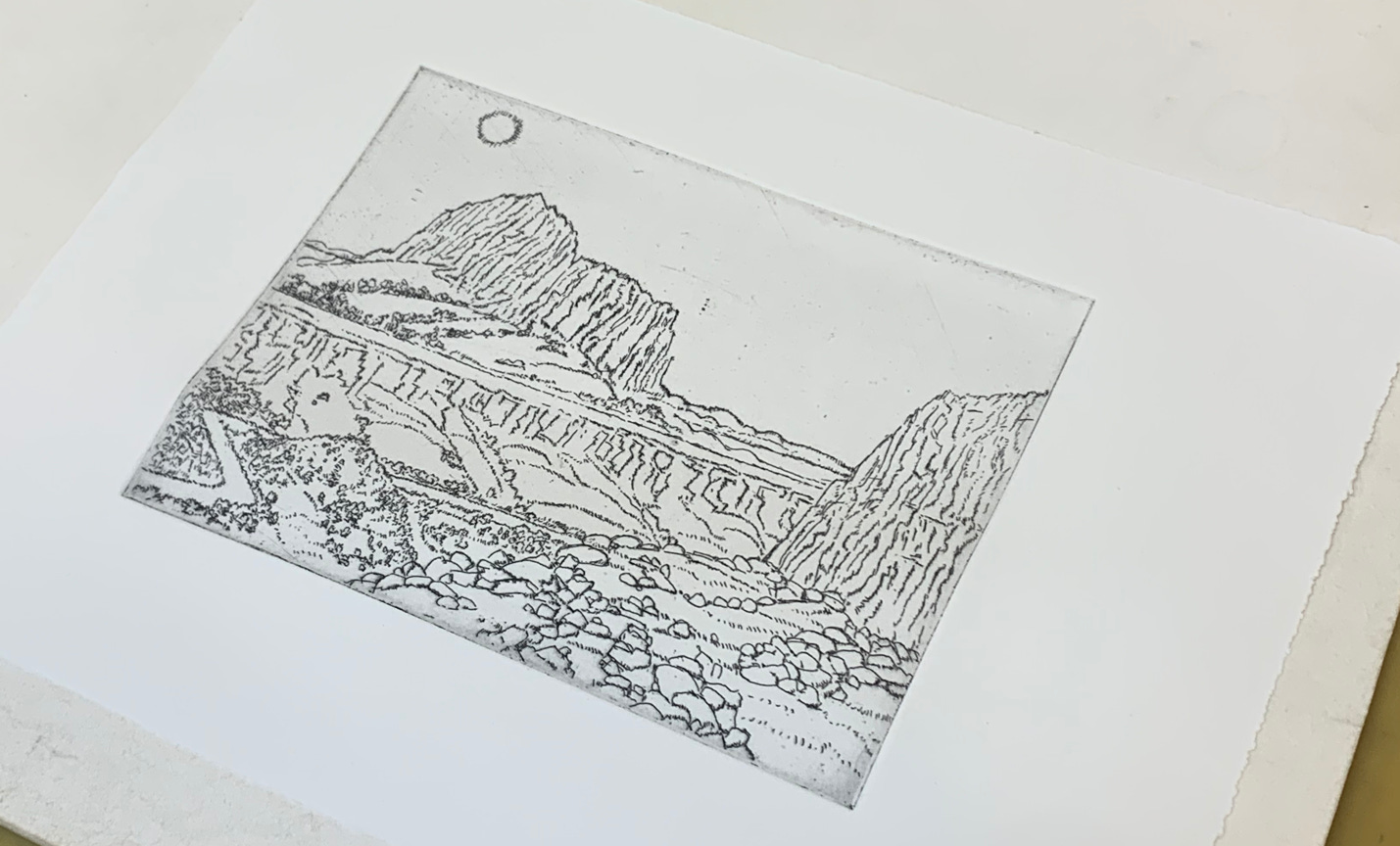

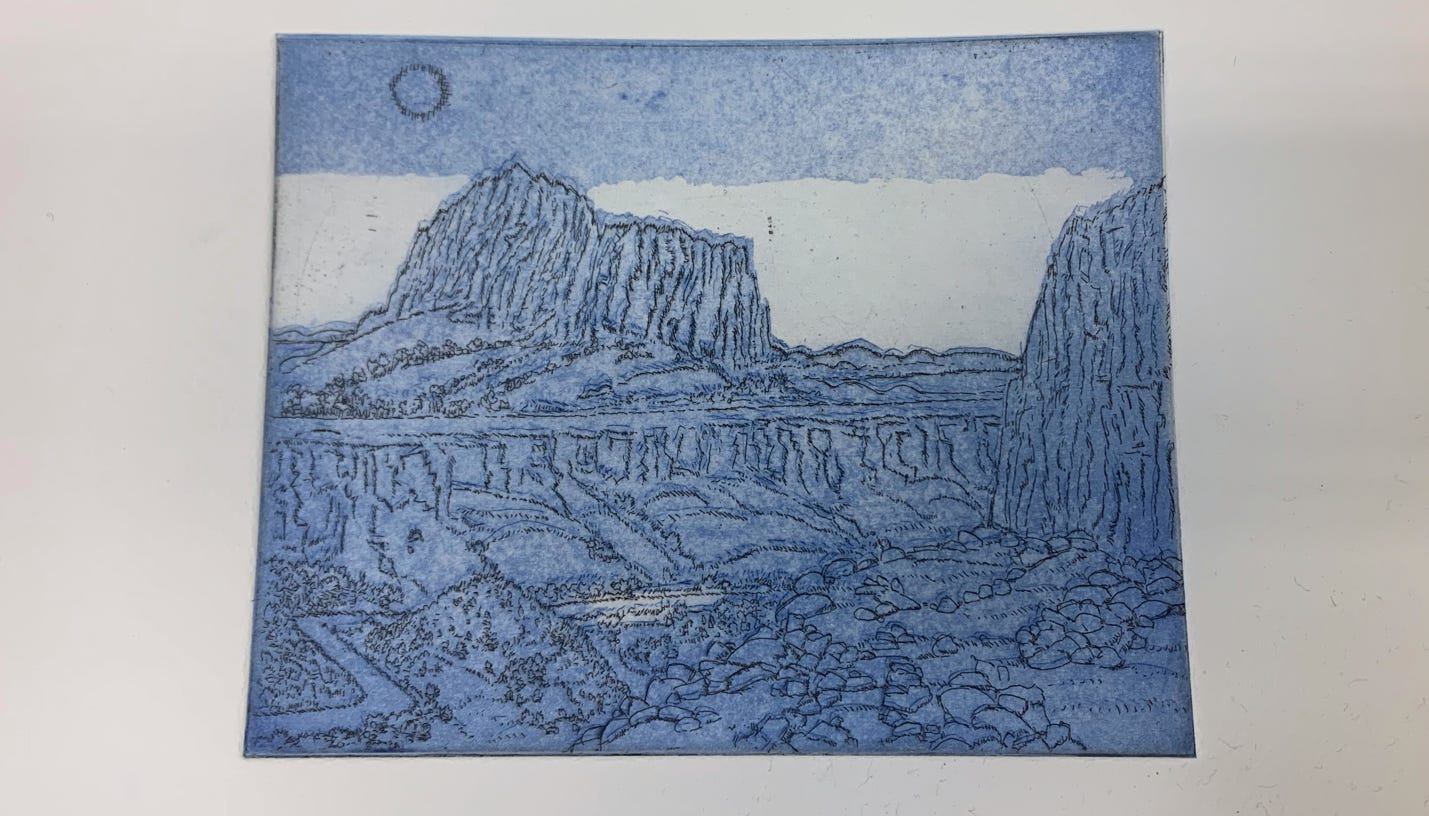

The first state of Desert Nocturne, getting a look at the linear bones of the image

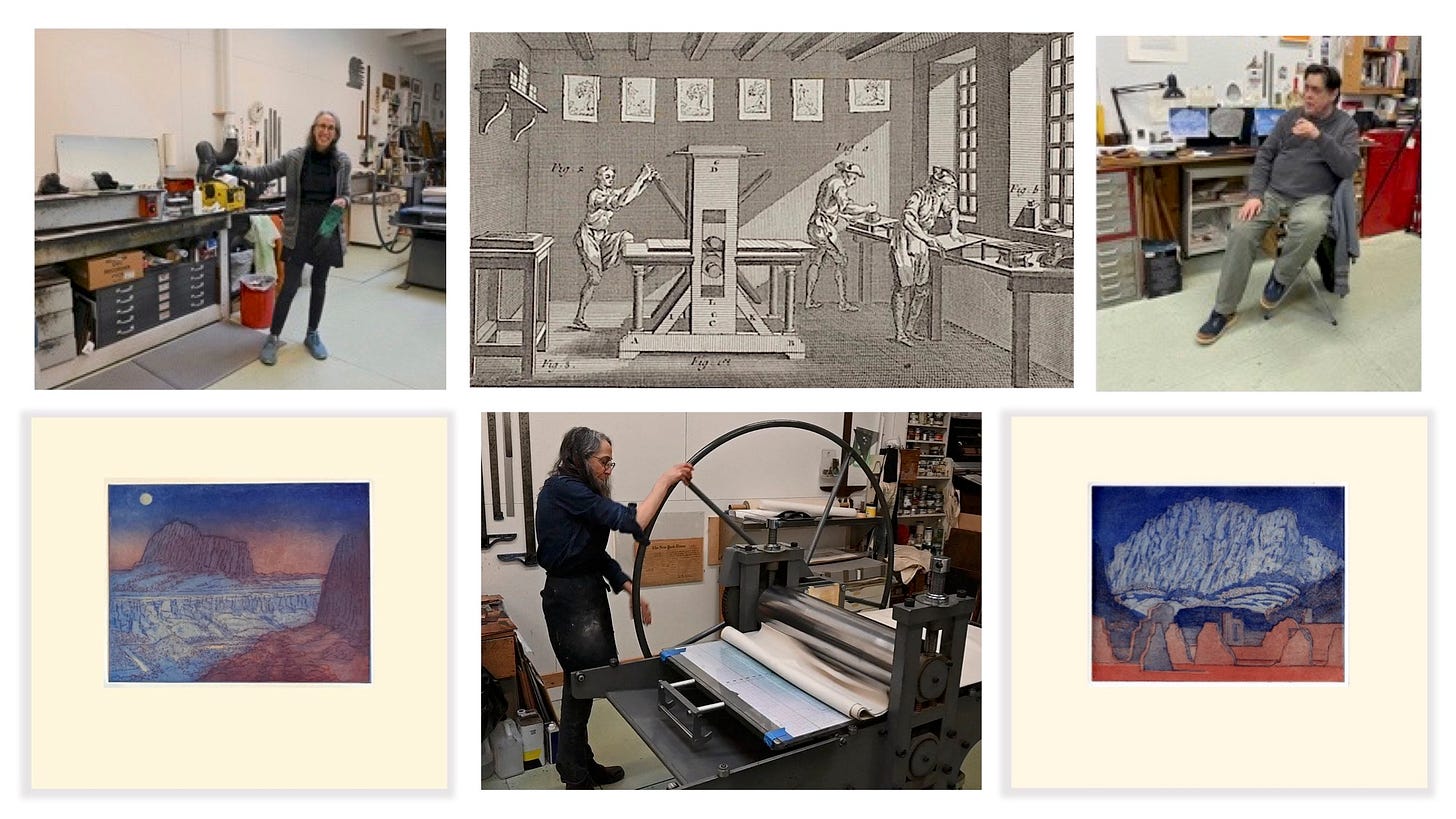

When the plate came out of the acid, Cindi stripped off the ground with mild solvents, wiped it down and proceeded to apply the ink. Printer’s ink is a thick, sticky substance that resembles tar as much as anything else. Warming the plate helps loosen the goop, which Cindi scraped across the surface with a cardboard squeegee; pushing the ink into the recesses. She then removed the surface residue with a ball of bunched-up muslin known as tarlatan. The fabric was developed to be used in airy tutus and diaphanous ballgowns. The word entered the English language by way of the Français tarlatane, which may have come from tarlatanna, in the Milanese dialect. Similar to cheesecloth in its stiffness and open weave, it is well-suited to picking up ink from copper plates. Areas that become filled with ink can be folded under, to expose an un-besmirched patch of fabric. A plate wiped clean with tarlatan will bear a slight, oily film known in the trade as plate-tone, which can be removed by the printer, or allowed to remain—for reasons to be explained later.

After dipping the heel of her hand in a shallow tray lined with talcum powder, Cindi brushes away the remaining residue with a light sweeping motion; taking care to keep chalky particles from entering the inked incisions. The plate is now carried to the press. Sheets of cotton laid paper produced by St. Cuthbert’s Mill in Somerset, England were prepared for printing first by soaking, then blotting, and finally resting in a waterproof nest of plastic sheets. Cindi gently grasps one of the sheets by its opposite corners, and lifts its onto the press

If intaglio printers and lithographers exhibit behaviors consistent with obsessive-compulsive disorder, it is because they know that a single stray particle of dust on a plate, or the slightest trace of ink on one’s fingers might ruin a perfect print. Once the paper is in position Cindi moves to the side of the press, and slowly turn’s the great captain’s wheel. She explains to me how the position of the plate, in relation to the grain of the paper, can yield different results—a subtlety which I can freely confess is well above my pay-grade.

Using cardboard pincers to peel back the print from the plate, Cindi lays it out on the press-bed. The aquatint had left a good, even bite, but with an abrupt transition between a dark sky and the lighter horizon. I softened the troublesome border with emery cloth and steel wool which lessened, but did not solve the problem. Cindi then proposed a risky remedy. A creeping bite is achieved by dipping a plate prepped for aquatint into the acid at an angle, letting the acid areas of the plate submerged longer will receive a deeper bite, and print a deeper tone. The second plate was simpler, as it lacked similar gradations.

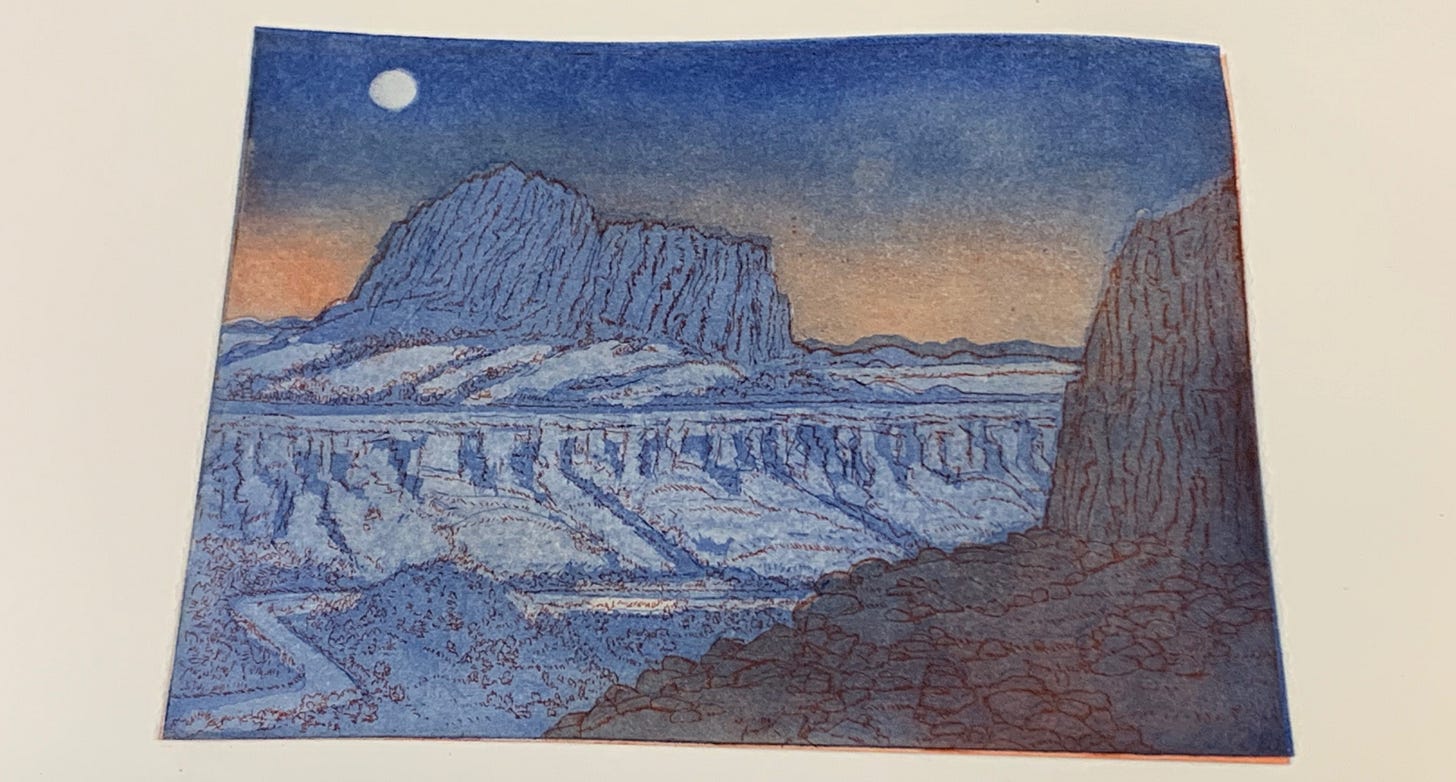

When Cindi printed the blue plate, and followed by the red plate, we could see that the creeping bite had worked. There were minor problems of alignment, but the challenge of achieving a smooth transition between the uppermost edge of the image and the horizon had been solved. I used a small spherical burnisher was to polish the plate in areas where aquatint borders strayed too far from the drawing.

Cindi was hesitant to layer more aquatints on top of what we had already done, because there comes a point at which the acid will burn the plate beyond its capacity to retain ink. What remains are rough, blank areas of indifferent texture. We rolled the dice once or twice, with no ill effects. We first attempted to replicate the orange lines of my sketchbook paintings, then tried vermillion, and then an earthen red. I prefer not to use colors taken straight from the tube, or in the case of printers’ ink—the can. Perhaps this can be attributed to past mentors, such as the late William Bailey, who insisted that mixing one’s own colors is essential to good painting. We settled on a mixture of Alizarin Crimson and Burnt Siena.

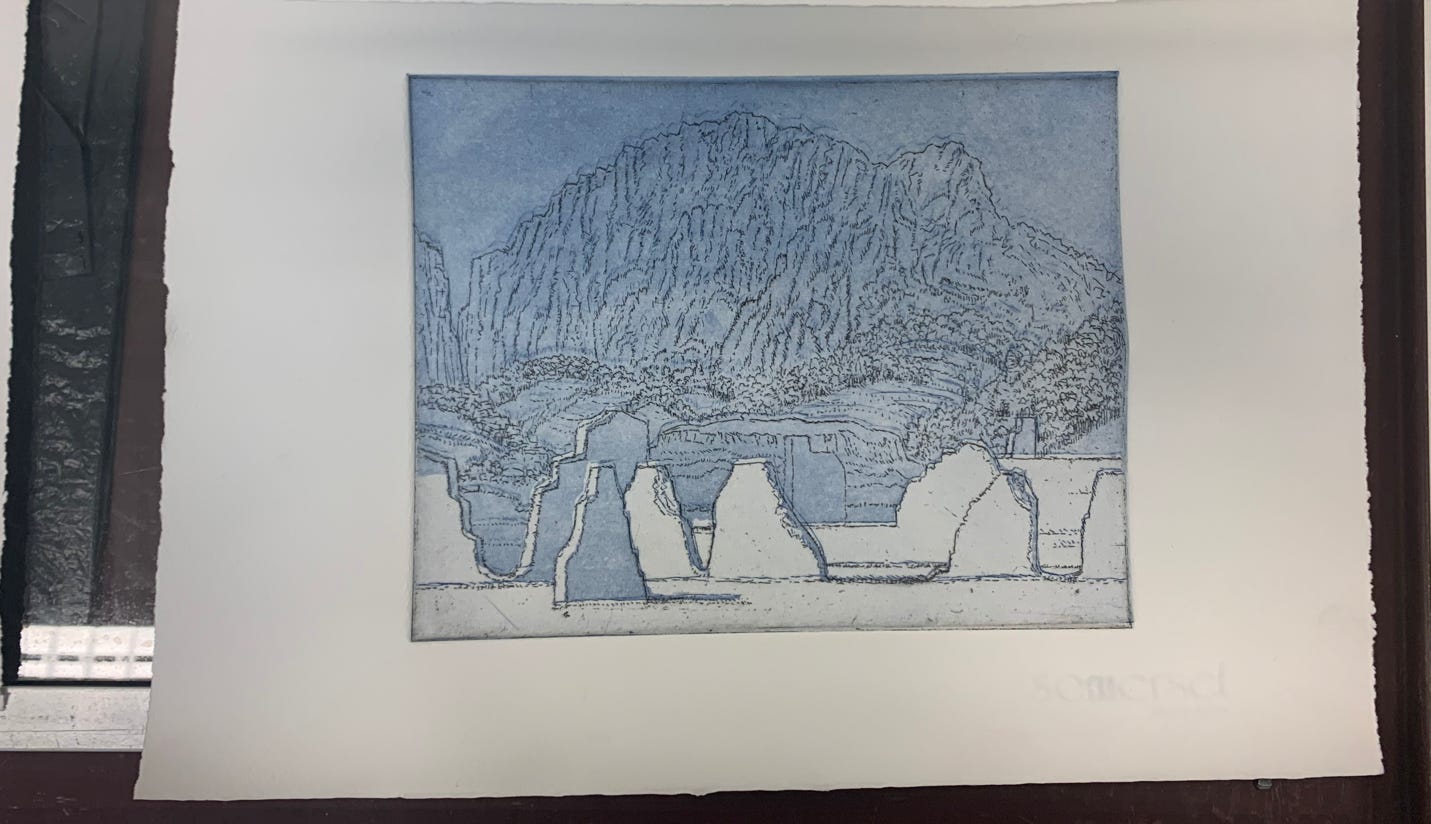

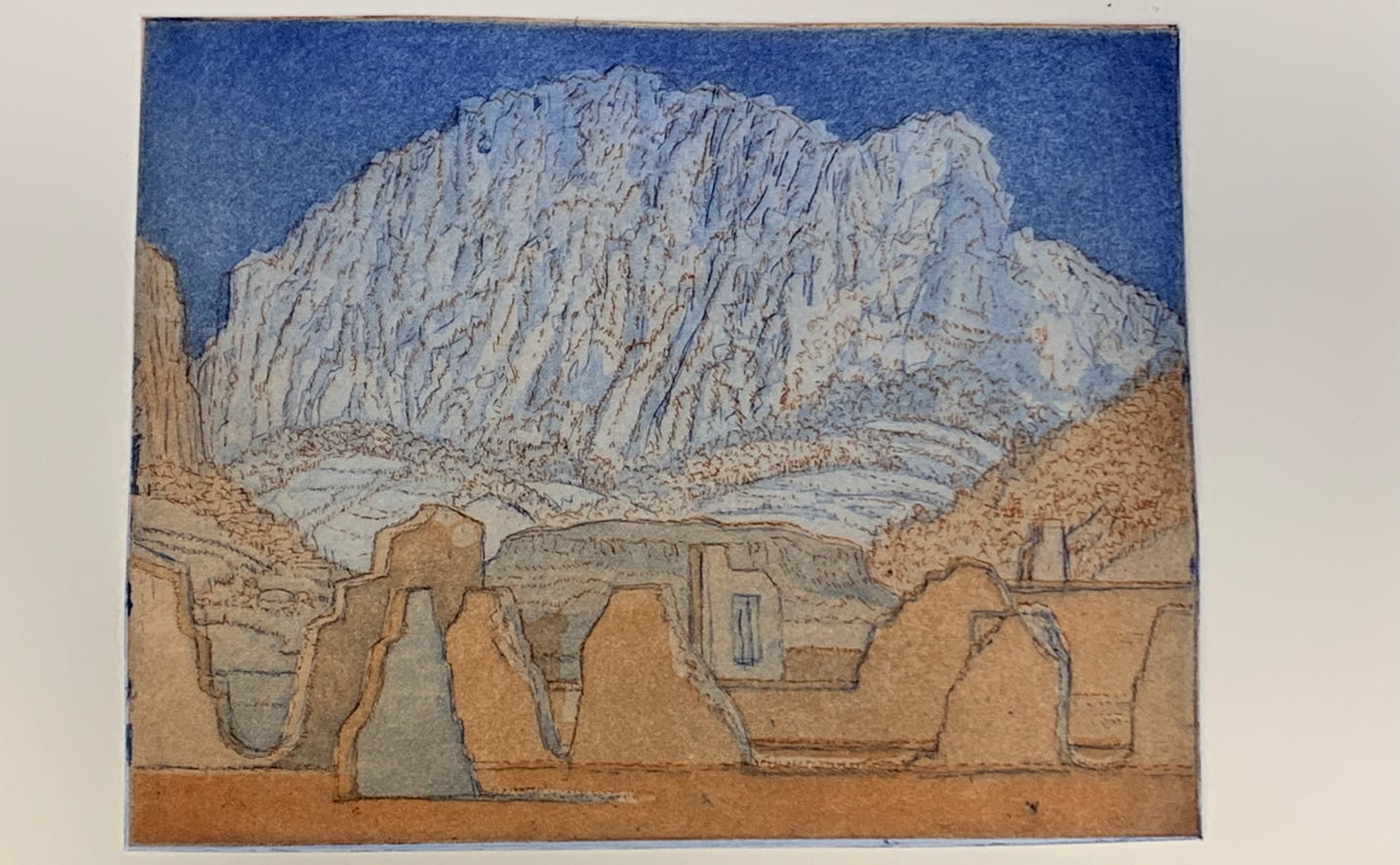

Mountain Elegy presented us with different difficulties. The intricacy of the image, combined with the compact density of overlapping forms needed to be broken up with subtle transitions in value. Being unable to keep building up aquatints we resorted to a technique known as spit bite, in which an acid solution is applied with a brush, directly onto the plate. Like the creeping-bite, it required a trust fall. One of the challenges is that where acid bites metal, a whitish foam appears, making it difficult to judge its effect. Rolling past four o’clock on Friday afternoon, we had three days behind us, and an hour to go before reaching the end of our session. Over the course of roughly 24 hours we had etched, scraped, abraded, burnished, inked, wiped, and printed two images with four plates. This was in addition to to the time I had spent developing the compositions as watercolors, transferring line-drawings of those images onto the plates, which I then inscribed. I commented to Cindi that it felt like we had just run the printmaking equivalent of a marathon—weeks of planning culminating in a burst of productivity. She had thought it a crazy plan, but felt satisfied with the results. The beauty of working collaboratively is that it leads us to places that we might never have found on our own.

(To be continued)

—James Lancel McElhinney © 2024

CLICK the image below to read about more printmaking experiences on SUBSTACK