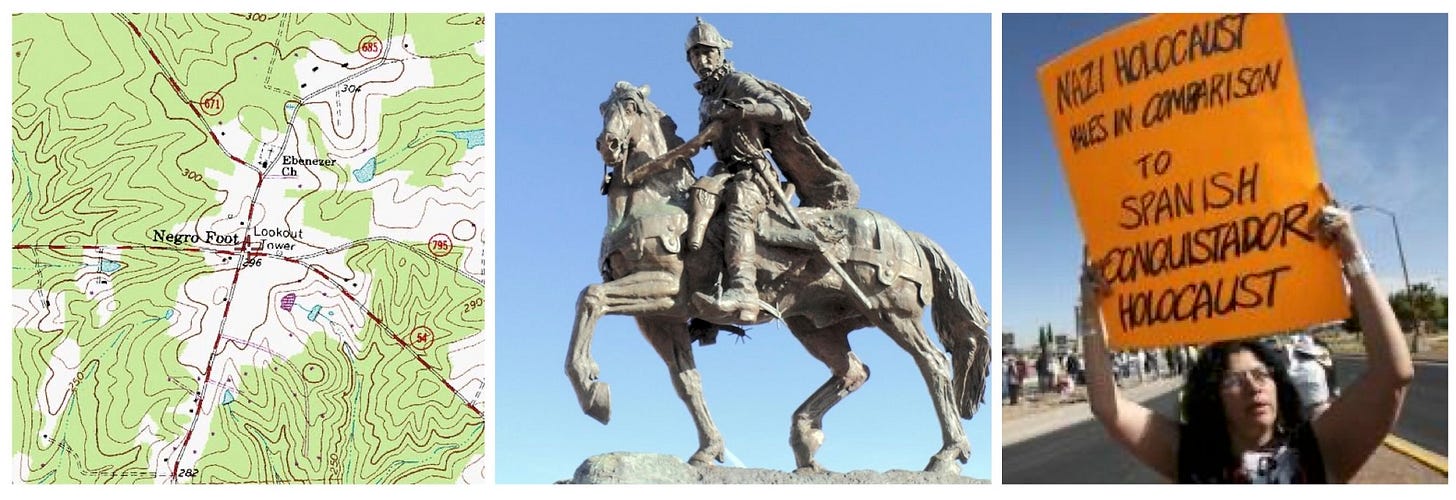

Thoroughfares in Virginia are named for Martin Luther King Jr., Maggie L. Walker, and Arthur Ashe, but I found only one toponym with the cringeworthy moniker of Negro Foot on historic maps, its name is even worse. The unincorporated community is centered on the intersection of Patrick Henry and Scotchtown roads in western Hanover County. Legend claims that a runaway was caught at the crossroads, where slave-catchers chopped off his foot. I wondered if that enslaved man’s name had been Kunta Kinte. Limb amputation was commonly used as a punishment in ancient China, Europe, and the Muslim world—where some countries continue the practice today. A thief might be deprived of a hand, or a runaway slave might lose a foot.

In 1599, a Spanish army led by Don Juan de Oñate y Salazar had besieged the mesa-top pueblo of Acoma. Upwards of 1,000 inhabitants were slaughtered. The town was put to the torch. When the survivors had been rounded up, Oñate ordered his men to chop off the right foot of every man over 25. In 1994, an equestrian statue of Spanish conquistador Juan de Oñate was installed outside of the Northern Rio Grande National Heritage Center in Alcade, New Mexico, in 1994. The monument was created by Reynaldo Rivera, as a symbol of Hispanic pride, in anticipation of the Quadricentennial celebrations planned for 1998. The Heritage Center staff arrived at work on December 30, 1997, to discover that Oñate’s right foot had been cut off, as retribution for the 1599 Acoma Massacre.A note was found beside the disfigured monument. On it was written “Fair is fair.” The bronze foot was eventually replaced, but the Oñate monument was removed in 2020, amid the storm of protests triggered by the death of George Floyd. Tensions between indigenous and ethnic Spanish communities flared, when Rio Arriba County planned to reinstall the embattled monument in the City of Espanola. A Hopi-Akimel O’odham environmental activist was wounded by a Hispanic shooter, during a nonviolent protest against the move. The 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville that left one bystander dead and nearly three dozen injured triggered a storm of protests that focused its ire on confederate monuments.

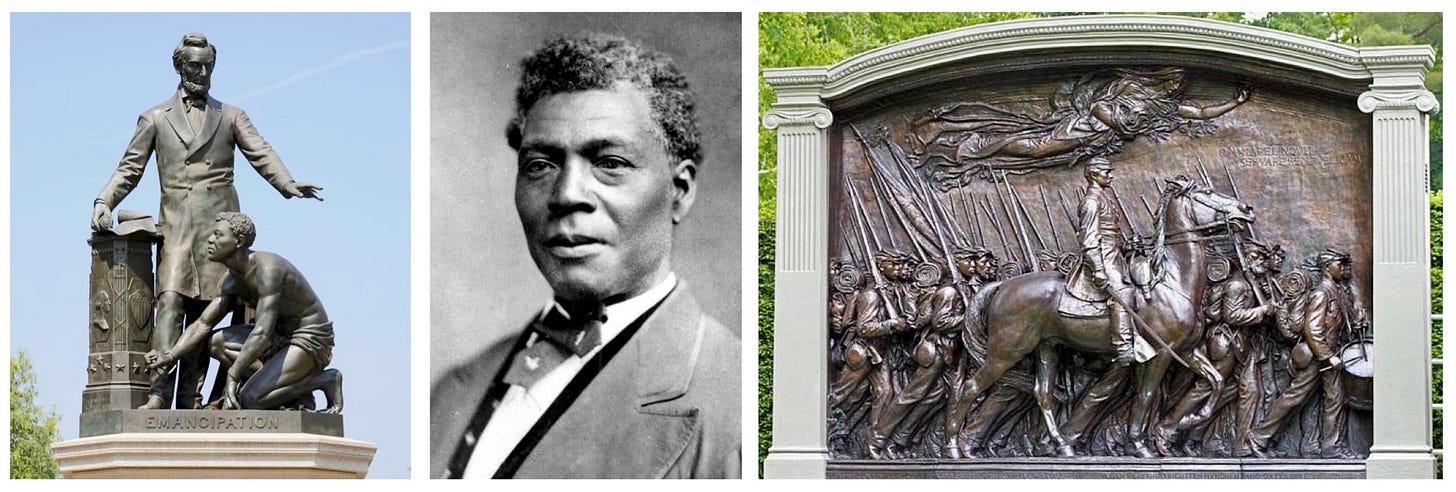

Iconoclastic fervor soon widened its scope. Thomas Ball’s Emancipation Memorial had been unveiled with great fanfare on Capitol Hill, in Washington D.C. in 1876. Abraham Lincoln stands holding the proclamation, beside a seminude black man, crouched at the president’s feet. Those attending the unveiling would have recognized the model for the kneeling figure as Archer Alexander, whose life story; The Story of Archer Alexander, from Slavery to Freedom, had been published in 1863 by educational reformer William Greenleaf Eliot—the grandfather of poet T.S. Eliot. Alexander’s great-great-great-grandson was famed boxer Muhammad Ali. Had the City of Boston known the backstory of Ball’s monument before it was removed on December 29, 2020, it might have found reasons to keep it in place. One wonders if the city was glad for an excuse to take down the sculpture.

Augustus Saint-Gaudens’ Shaw Memorial may be the finest public artwork in America. Robert Lowell describes it in his poem For the Union Dead.

Two months after marching through Boston half the regiment was dead; at the dedication, William James could almost hear the bronze Negroes breathe.

Their monument sticks like a fishbone in the city's throat. Its Colonel is as lean as a compass-needle.

A bust of General Grant was attacked in San Francisco. A member of the New York City Public Design Commission the following year called for a purge of all male-gendered statuary in Central Park. Only the portrait of controversial physician Marion Sims was removed in 2018, following revelations that Sims had used enslaved women as guinea pigs for his gynecological experiments. New monuments to women were commissioned instead, as a move toward parity. Meredith Bergman’s Women’s Rights Pioneers Monument was dedicated in 2020.

The equestrian Theodore Roosevelt Memorial had stood from in front of the American Museum of Natural History on Central Park West since 1939. The 26th president of the United States is portrayed with a bodybuilder physique, attended by two figures on foot—a warbonnet-wearing Plains Indian on his right, and an African on his left. The implied subservience of these people of color led to its removal in December, 2022, a little over a year since Richmond’s Robert E. Lee Monument by Antonin Mercié had been dismantled. Merciéhas received the commission through his friendship with Augustus Saint Gaudens, whose monument to William Tecumseh Sherman stands at the southeast corner of Central Park. The general stride his warhorse Duke walks behind the goddess of Victory. A southerner was reported to have said, upon seeing the statue, “Isn’t that just like a Yankee, making the lady walk?”

When Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial was dedicated in 1982, the aesthetics of public remembrance had already evolved from tombstone statuary to memorial parks. Sir Edwin Luyten’s Memorial to the Missing of The Somme was dedicated in Thiepval, France, fifty years prior. Carved on the walls of Luyten’s grand arches are the names of 72,337 British and South Africans whose bodies were never recovered. The Sacrario di Asiago designed by Orfeo Rossato was opened to visitors in 1938. It contains the remains of more than 50,000 Italian and Austrian soldiers killed on the Altopiano di Sette Communi. These are monumental structures, surrounded by open spaces. Maya Lin’s memorial might be likened to an alfresco basement for one of these buildings—into which visitors descend beside a long black wall, inscribed with the names of the dead. Three Soldiers by Frederick Hart was unveiled two years later, in response to objections by veterans demanding a more fitting tribute to their fallen comrades than what Tom Wolfe described as a “pitiless tombstone.” Some may lament its disparity of artistic styles, but the juxtaposition completes this memorial landscape, which attracts more than five million visitors each year.

Today’s self-described defenders of western culture hasten to gird our coastlines with drilling platforms, ramp up production of domestically-sourced fossil fuels, and lease out national forests to logging. We’ll see how the present administration reconciles these plans with its calling for the Department of the Interior to,

“. . . focus on the greatness of the achievements and progress of the American people or, with respect to natural features, the beauty, abundance, and grandeur of the American landscape.”

Government threats to clear-cut national woodlands are nothing new. Ronald Reagan’s Secretary of the Interior James G. Watt endorsed a similar course of action. Watt also delayed the construction of Maya Lin’s veterans’ memorial, not because it was avant-garde, but because represented non-western traditions of which he knew nothing—such as Egyptian mural reliefs and Chinese wall inscriptions. Frederick Hart’s Three Soldiers is a reiteration of Beaux-arts aesthetics, and the European tradition that has lately come under attack as colonizer culture, but according to poet Frederick Turner, tradition demonstrates its fitness by standing the test of time. Turner cleverly invokes the Second Law of Thermodynamics in his book The Culture of Hope, to argue that whatever represents less radical must generate less entropy, and thus prove more durable. In other words—if something ain’t broke, why fix it?

In an Executive Order signed by President Trump on March 27, 2025, the U.S. Secretary of the Interior has been charged with the task of determining if,

“. . . public monuments, memorials, statues, markers, or similar properties within the Department of the Interior’s jurisdiction have been removed or changed to perpetuate a false reconstruction of American history,” and to “take action to reinstate the pre-existing monuments, memorials, statues, markers, or similar properties.”

While the order applies only to federal property, it is likely to embolden state and local governments—especially in the south—to reverse prohibitions against displaying confederate flags, and to restore confederate monuments to the public parks and courthouse squares from whence they were removed. The statue of Robert E. Lee had been a rallying-point for the Unite the Right rally in 2017. Charlottesville City Council ordered its removal from Market Street Park in 2021, and melted down two years later, with the bronze to be used to create a “more inclusive” monument to the community, through Charlottesville’s new Swords into Plowshares RECAST/RECLAIM project.

Myth-making is part of what government does, at every level. There is an old Soviet joke that “The future is certain, Only the past is unpredictable.” Battles that rage over America’s collective memory will continue to keep us together.

My sister-in-law worked for Richmond’s Catholic-sponsored refugee resettlement services. One of her Vietnamese beneficiaries asked about the statutes on Monument Avenue. Carol explained that they honor southern leaders in the American Civil War. He asked if those men had won the war. No, she replied, they lost. The idea of raising monuments to the defeated perplexed her client, but explaining Jim Crow racism to a newly-arrived person of color might have upset their American dream. Defacement and toppling is what all monuments risk, as societal value change. Destroying memorials to tyrants will not erase the memory of their crimes. Killers can obliterate their fingerprints, without losing their bloody hands. Nazi symbols are now banned in many countries around the globe, but protections of free speech in Britain and the United States extend even to those who would deny the right to others. Some might argue that obsolete monuments have instructional value—like rotting felons hanging in chains. Being forced to remember unpleasant times can help to dissuade us from repeating past mistakes. If damnatio memoriae becomes our default response to whatever in history offends us, we may be welcoming future disasters by nurturing deeper intolerance. In Giuseppe di Lampedusa’s epic novel Il Gattopardo, the conservative prince Don Fabrizio asks why his nephew follows Garibaldi. Tancredi replies, “Se vogliamo che tutti rimanga come,’ bisogna che tutti cambi.” If we want everything to stay the same, everything must change.

(To be continued)

—James Lancel McElhinney © 2025

Please consider the benefits of becoming a PAID subscriber, including access to serialized articles such as SKIN IN THE GAME: Personal Notes on Valuations, Appraisals and Marketing, for Artists, Buyers, and Collectors: