“. . .landscape is not a natural feature of the environment but a synthetic space, a man-made system of spaces superimposed on the land, functioning and evolving not according to natural laws but to serve a community. . . A landscape is thus a space deliberately created to speed up or slow down the process of nature. As Eliade expresses it, it represents man taking upon himself the role of time.”

In 1984 John Brinckerhoff Jackson took umbrage with the conventional definition of landscape as, “. . . a portion of the land which the eye can comprehend at a glance.” Jackson argues that that the term landscape “. . .did not mean the view itself, it meant a picture of it, an artist’s interpretation. It was his task to take the forms and colors in front of him—mountains, river, forests, fields, and so on—and compose them so that they made a work of art.”

—John Brinckerhoff Jackson

Forty years later, this definition is not only defunct. It is counterproductive. Environmental changes now underway demonstrate how mankind’s attempts to dominate nature have now put its control even further out of reach.

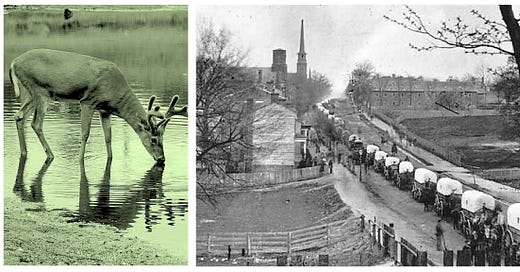

During a guided tour of Gettysburg, or maybe it was Chickamauga, the ranger leading the group was asked why Civil War battles were fought in national parks. This humorous story is probably apocryphal, but I once was asked why so many of Virginia’s battlefield took place near interstate highways. My reply was that like all animals, deer need water. A person cannot survive without water for more than three days, or four at the most. A prey animal drops its guard by dipping its head in a creek. To lessen its chances of being taken by predators, the deer might find a safer place to drink in wide, shallow sections of the stream, which form just upstream of falls. Pebbles and silt carried downstream pile up behind declivities over which waters descend. Flooding widens the stream; undercutting its banks. Times passes, until bipedal hunters stalk these watering-places, transforming game trails into well-trodden footpaths. Travelers and war-parties wade through the shallows, which soon become fords. Europeans arrive in the 17th century. Footpaths expand into roads, to accommodate horse-drawn conveyances. A bridge is built near the ford before long, pinning the meandering watercourse to a static location. A new road is built two hundred years later, alongside the old thoroughfare to carry more traffic, and give repairmen access to newfangled telegraph wires. Because Civil War armies used the new roadway to move troops and materiel, its control was hotly contested. The appearance of automobiles decades later made way for a new two-lane blacktop, built beside its macadamized predecessor. The old Telegraph Road was used to deliver materials and road-crews to worksites along the route. Like its ancestral cartways, footpaths and game trails, it too was abandoned, and soon disappeared under second-growth forests, housing developments, and roadside businesses. On June 29, 1956, president Dwight D. Eisenhower signed legislation authorizing the creation of an interstate highway system. The Virginia section of I-95 opened to high-speed vehicular traffic in the following year. Its route follows falls lines across Virginia’s Rappahannock, Mattaponi, Pamunkey, Chickahominy, James, Appomattox, and Meherrin Rivers, and the Roanoke, Tar, and Neuse Rivers in North Carolina. The pathways of 21st-century rights-of-way thus were predicated not by human decree, but by the behavioral patterns of quadruped mammals, struggling to survive in hostile terrain being shaped by the forces of nature.

Puritan preacher Cotton Mather states that “Wilderness is a temporary condition through which we are passing to the Promised Land,” resonates with Captain John Smith’s claim that “. . .God did make the world to be inhabited with mankind.” While Mather regarded uncolonized land as The Devil’s domain, Smith saw it as a bounteous realm, where fish leaped out of the river into frying pans and “. . . for a copper knife and a few toys, as beads and hatchets, they (the indigenous people) will sell you a whole Countre (sic).” Both men’s assertions are rooted in passages from the Book of Genesis:

“And the LORD God formed man of the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and man became a living soul.”

The word human—like landscape—may also be interpreted in a number of ways. Perhaps the most reasonable etymology is a combination of the Latin word for man—homo, with the Latin word for the ground—humus, into the compound neologism humanus, or humano, which translates as “human” in English. Shortly after the creation of Adam, verse 19 states that,

“. . .out of the ground the LORD formed every beast of the field, and every fowl of the air. . .”

Both man and beast were formed “out of the ground,” and yet only the progeny of Adam claims to be human. In fact all that were born of the soil fight tooth and nail overs its dominion, with mankind at the head of the food chain, except from time to time when polar bears and crocodiles fill their bellies with human flesh. Theologians will forever debate the true nature of original sin—the eating of forbidden fruit, and then passing the buck to one’s sidekick. The history of mankind chronicles an epic concatenation of overreaching blunders and shirked responsibilities. My wife and I share 75% of our DNA with our feline roommate, and completely agreement with the late Pope John Paul II, who declared in 1990 that animals are as close to God as human beings. Whatever one’s religious belief may be, we are all sentient beings, composed of flesh, bone, and blood. It might be best to embrace the idea that being human is being one with the earth, and that living things are our kin.

The secretariat of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) has articulated The Rights of Nature (RoN),

“. . . as a legal instrument that enables nature, wholly or partly, i.e. ecosystems or species, to have inherent rights and legally should have the same protection as people and corporations; that ecosystems and species have legal rights to exist, thrive and regenerate. It enables the defense of the environment in court – not only for the benefit of people, but for the sake of nature itself.”

Returning to J.B. Jackson’s definition of landscape as something that occurs not in nature, but is created when human beings adapt natural spaces to their use, the scenery we behold is nothing more than our own desires, inscribed upon the terrain. The mountains, waters, forests, farm-fields, bogs and deserts; and all the creatures abiding within them are not out there. They are part of our corporeal being. Landscape is thus a reflection of who we are.

—James Lancel McElhinney © 2024

NB: Please pardon any errors or omissions, which shall decrease when a sufficient number of paid subscribers generates sufficient funds to pay my talented editor.

A note to readers: If you are a paid subscriber, I am deeply grateful for your support. If you are a free subscriber, thanks for following me, and please consider upgrading your subscription from free to paid for just $5.00 a month paid

Further reading:

John Brinckerhoff Jackson. Discovering The Vernacular Landscape. Yale University Press, New Haven. 1984

Really intriguing blend of concepts. My association with “landscape “ is twofold. Working with contractors who manipulate the land, I think of landscaping as a verb. Alternately as an artist I attempt to convey ( usually badly!) my emotions as I view any tiny slip of nature on canvas, paper, clay.

My experience of land “scape” is experiential rather than educated: I know what I feel rather than see, rather than what I can read. I know I as a living being, I am part of earth. How can I be otherwise? I also know as a contemporary human, I divorce myself from myself by working always indoors, by driving constantly, by eating foods out of season… you get the point. Growing up in NYC, my separation from landscapes was nearly total. I had cityscape.

I have no particular religion, but I lean towards animism. Perhaps that glacial boulder in Central Park, with heavy striations from glacial debris scraping over it endlessly, has every and the same right- place?- as I to be in the park, taking the sun, listening to NYC traffic and feeling the air on my skin.