People sometimes ask me why everyday folks should care about art, when only the rich can afford it. My reply was that all kinds of art possess the capacity to transform the terror and mayhem of human existence into experiences that inspire, uplift, and sustain us. Art also provides comfort—like a functioning air-conditioner in the dog days of summer. It can alleviate stress, calm one’s mind, and stir the imagination. Art enhances problem-solving, by showing us how to look at things with a creative eye. Learning how sharpens our understanding of the world around us, and find our place in it. Other than that, it’s useless. Oceans of ink have been spilled in attempts to define what art is, when all that matters is what it can do.

Sorting through hundreds of paintings I hadn’t look at in decades; some of which I forgot having made, ambushed me with unexpected insights. Most of the landscapes I had painted over the years had been sold. Only a handful have come up for auction, which could mean that works I sold are now treasured heirlooms, or gathering dust in bric-a-brac shops. An interesting painting turned up in a Hudson Valley antiques store fifteen years ago. The picture faced the wall, in stack of paintings at the back of the shop. Its maker had been given a show by Marcia Tucker. Less than thirty years after it debut at The New Museum, the painting gathered dust, outside a sketchy powder-room. At a New England flea market I spotted a large pastel of a nude woman, by a known Philadelphia artist. The piece had been framed professionally, presumably for display in an upscale home. It was propped up in bright sunlight, between a table-leg and dew-soaked turf. Drops of condensation had begun to form inside the glass. It was heartbreaking to see something made with great care destroyed with such gross disregard.

My old paintings emerged from boxes and soft-packed wrappings like surplus mummies. I was stunned by the quantity of packing-material that was shed in the process. Coming to light were hundreds of nudes; running the gamut from chaste portraits and rooftop sunbathers, to postmodern Síle na gcíoch. The majority were from the 1980s and ‘90s. Beginning with my debut as a teaching assistant to Bernard Chaet at Yale in 1975, to retiring from teaching in 2016, life drawing had always been one of my strengths. Because working with nude models was central to my teaching, mastery of the process was essential. Models were hired for private sessions when I could afford it, or the cost was sometimes shared with other artists.

My wife Kathie Manthorne says that I hired life models to keep me company, which is probably partly true. Like tennis doubles of rounds of golf, group drawing sessions were also social gatherings. Silent obedience was never demanded of my sitters, with whom I would engage in sprawling discussion of books, movies, history, and politics. A few might confide deeply personal matters, such as medical woes, or love-life complaints. Painters working with models can become secret-sharers. As with hairdressers, barmen, priests, or shrinks, a level of trust can develop; like that shared by trapeze artists, actors, dancers. Art-models are in fact performing artists, but seldom acknowledged as such. Life-drawing classes at The Art Students League of New York fittingly end, with a round of applause for the model.

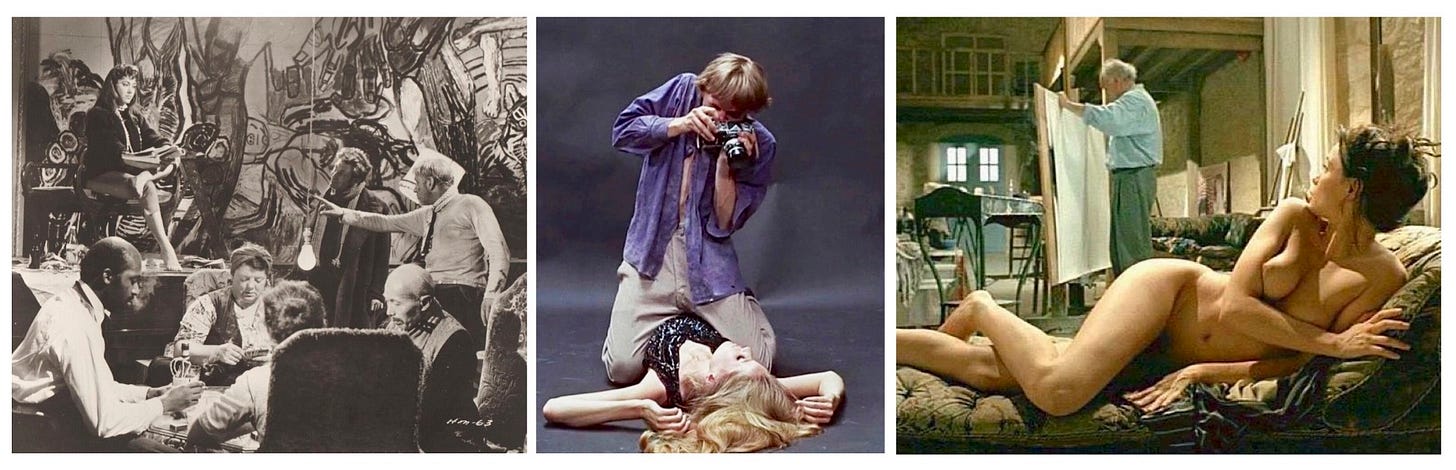

A question arises. If we regard models as performing artists—like actors, dancers, and professional wrestlers—instead of just living props for visual artists, shouldn’t their names be on the marquee? Artists’ models have enjoyed celebrity status, from the mythical Galatea, to the historic Nefertiti, Phryne of Athens, Campaspe of Larissa, Simonetta Vespucci, Veronica Franco, and the actress Nell Gwynn. Modern-day models such as Victoirine Mereunt, Suzanne Valadon, and Paula Moderson-Becker worked both sides of the easel, as both sitter and painter. Actors Clara Bow, Charlton Heston, and Barbara Stanwyck all worked as life-models during their rise to fame. A tragic archetype was popularized by George du Maurier’s fictional Trilby O’Ferrall, Rudyard Kipling’s Bessie, in The Light That Failed, and Blanche Stroeve in Somerset Maugham’s The Moon and Sixpence. Gillian Vaughan’s portrayal of Lille in Ronald Neame’s 1956 film The Horse’s Mouth mines the bohemian trope for laughs, while David Hemming’s photo-shoot pas-de-deux with Veruschka von Lendorff (who later pioneered body-painting) gave the art-model stereotype a makeover in Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1966 thriller Blow Up. Emmanuelle Béart’s character “Marianne” in Jacques Rivette’s film La Belle Noiseuse(1991) is cajoled into posing nude for an elderly painter played by Michel Piccolli. Jane Birkin, who plays the artist’s wife and former model, had her acting debut in Blow Up. Béart and Piccolli’s work-sessions become a battle of wills that end with Marianne starting a new life, and the painter confronting his own fading powers. While actors in these films only pretend to be painters and their models, there is plenty of role-play in real life settings. Thirty years before TikTok and Instagram, none of us could foresee how digital technology would transform so many of us into performers, in a relentless spectacle of hambone theatrics

In 1987 the National Endowment for the Arts awarded me a generous grant, which funded a series of paintings that employed multiple models. My disregard for how the art-market might receive them was rewarded with critical success and commercial failure. I was taken aback when feminist colleagues decried my new pictures as tainted by the male gaze. John Berger unpacked the concept in Ways of Seeing—not to chasten men who painted women, but as a riposte to the 1969 BBC television show Civilization, presented by Sir Kenneth Clark. Unlike today, discussions about art in those days seldom mentioned money. Artists instead imagined themselves like Berger and Clark—engaged in lofty discourse about culture, content, and style. Art-critical jousting was a sport we had learned in art-school critiques and thesis defenses. We believed that it advanced one’s creative practice, just as physical exercise enhanced one’s good health.

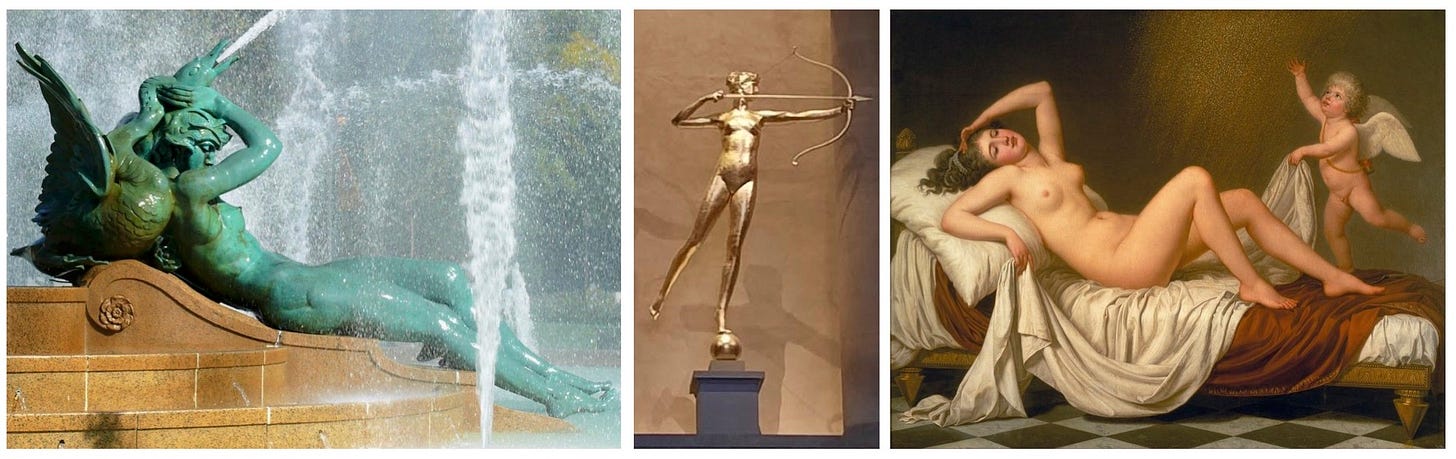

We looked to the leading figurative painters of the day, such as Lennart Anderson, William Bailey, Jack Beal, William Beckman, Gregory Gillespie, Alfred Leslie, Alice Neel, Philip Pearlstein, Joan Semmel, and Wayne Thiebaud; all of whom showed in New York. Plenty of other serious painters kept busy in other urban centers, but Philadelphia was notable for having the largest number of outdoor public sculptures in the country, and many of them were nudes. Adolf Ulrick Wertmuller (1751-1811) broke new ground when his Danaë went on view in Philadelphia; the first painting of a female nude shown to the American public. Students in life-drawing classes at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, and members of the Philadelphia Sketch Club drew from nude models. Owing to their city’s longstanding reputation as a center of center of science and medicine, depictions of undraped humans were less controversial than elsewhere. When Stanford White’s Madison Square Garden was razed in 1925, its scandalous weathervane—a 14-foot-high nude of the Roman goddess Diana—was installed in the newly-constructed Philadelphia Museum of Art, where it remains on public view.

How Philadelphia became a “city of firsts” was chronicled by Sid Sachs’ 2020 exhibition and book Invisible City: Philadelphia and the Vernacular Avant-Garde 1956-1976. Despite its proximity to New York, or perhaps because of its affordability, Philadelphia emerged as an incubator of figurative art during the 1980s, under the mentorship of Arthur da Costa, Larry Day, Martha and Walter Erlebacher, Zenos Frudakis, Sidney Goodman, Ben Kamihira, John Moore, and Neil Welliver. This burst of creative energy launched the careers of Bo Bartlett, Vincent Desiderio, and a new generation of teaching artists, of which I was one.

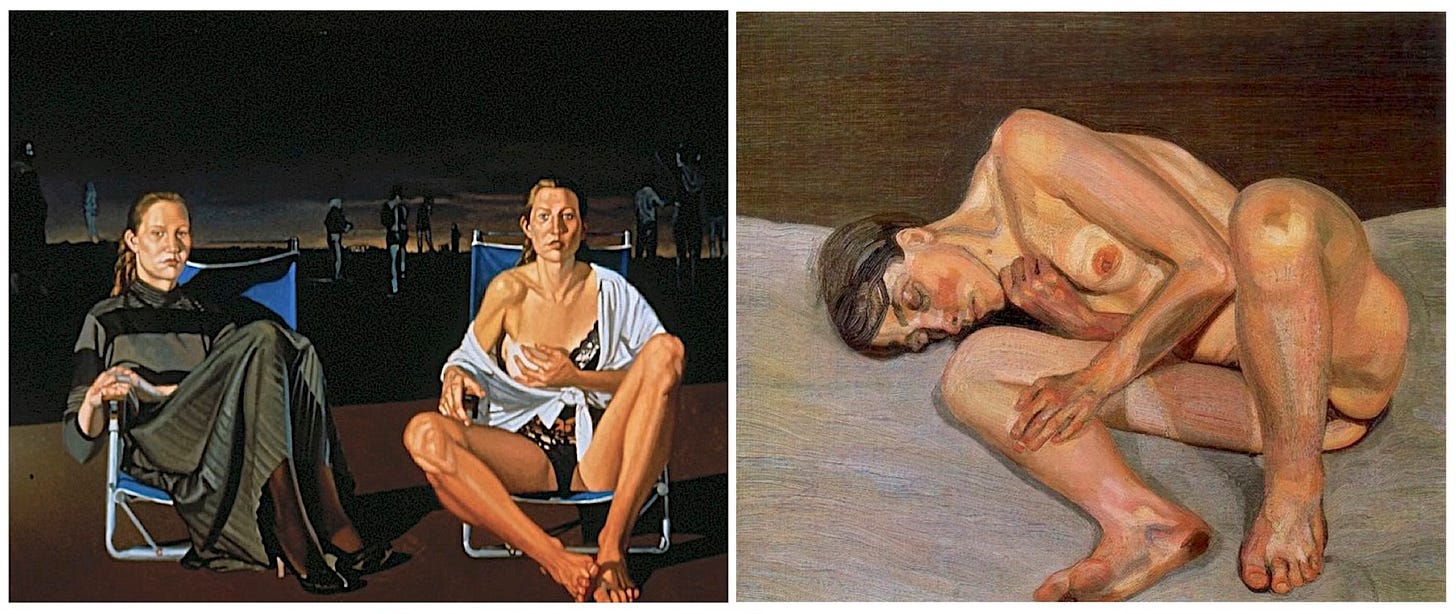

Lucien Freud’s 1987 retrospective at The Hirschhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden was a revelation. I was struck by the artist’s frank, carnal approach to the nude. Most museum tombstone labels placed beside paintings seldom identified models by name. Freud had done so, to stress that his nudes were in fact portraits. My traveling companion that day was fellow painter Sarah McCoubrey, who posed tough questions about irksome clichés that can pester interactions between artists and models. Painting both women and men with equal affection, indifference, and eroticism, Freud sidestepped objections to male-gaze objectification by celebrating the body; warts and all. Because many of my figure paintings were also portraits, I decided to pivot more in that direction, working in collaboration with my sitters.

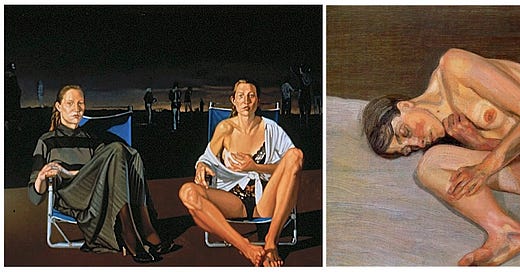

In Sacred and Profane Love at the Fountain of Venus (Villa Borghese, Rome) painted by Titian in 1514, two identical women sit beside a small marble fountain. One is bejeweled and attired in the most fashionable raiment. She represents the material (profane) world, while the nudity of her companion symbolizes the incorruptible (sacred) spirit. Several women friends agreed to reenact their own versions of the scene, according to their own interpretation of it. Each sitter was given a reproduction of the painting. They art-directed their own poses, of which I made rehearsal drawings. Two of these poses were selected to appear in paintings that measured 72 by 96 inches. Each depicted a sitter fully-clothed, beside a semi-nude portrait, sitting side-by-side in identical beach-chairs, against a dystopian backdrop. A pair of doppelgängers look out at the viewer, as each ponders their own self-image.

A movie-director friend suggested that Buck Henry elevator pitches for the Sacred and Profane paintings could be “Nine-to-Five meets Aviance Night by Prince Matchabelli,” “Schoolmarm Jekyll and Hot Ms. Hyde,” or a The Patty Duke Show reboot directed by John Waters or David Lynch. A dash of absurdism would have been palatable, perhaps seasoned with a bit less irony. The women who sat for the paintings had wielded unprecedented agency throughout the process, but perhaps that was not enough. By the time these paintings were shown at galleries in Philadelphia and Chicago in 1988, I had begun to explore a more collaborative approach that would launch a new series.

(To be continued)

—James Lancel McElhinney © December 23, 2024

NB: All images that appear with this article are reproduced under Fair Use, etc.

READ episode #103 b y clicking HERE