Palimpsest: /păl′ĭmp-sĕst″/: writing material (such as a parchment or tablet) used one or more times after earlier writing has been erased, or: something having usually diverse layers or aspects apparent beneath the surface.

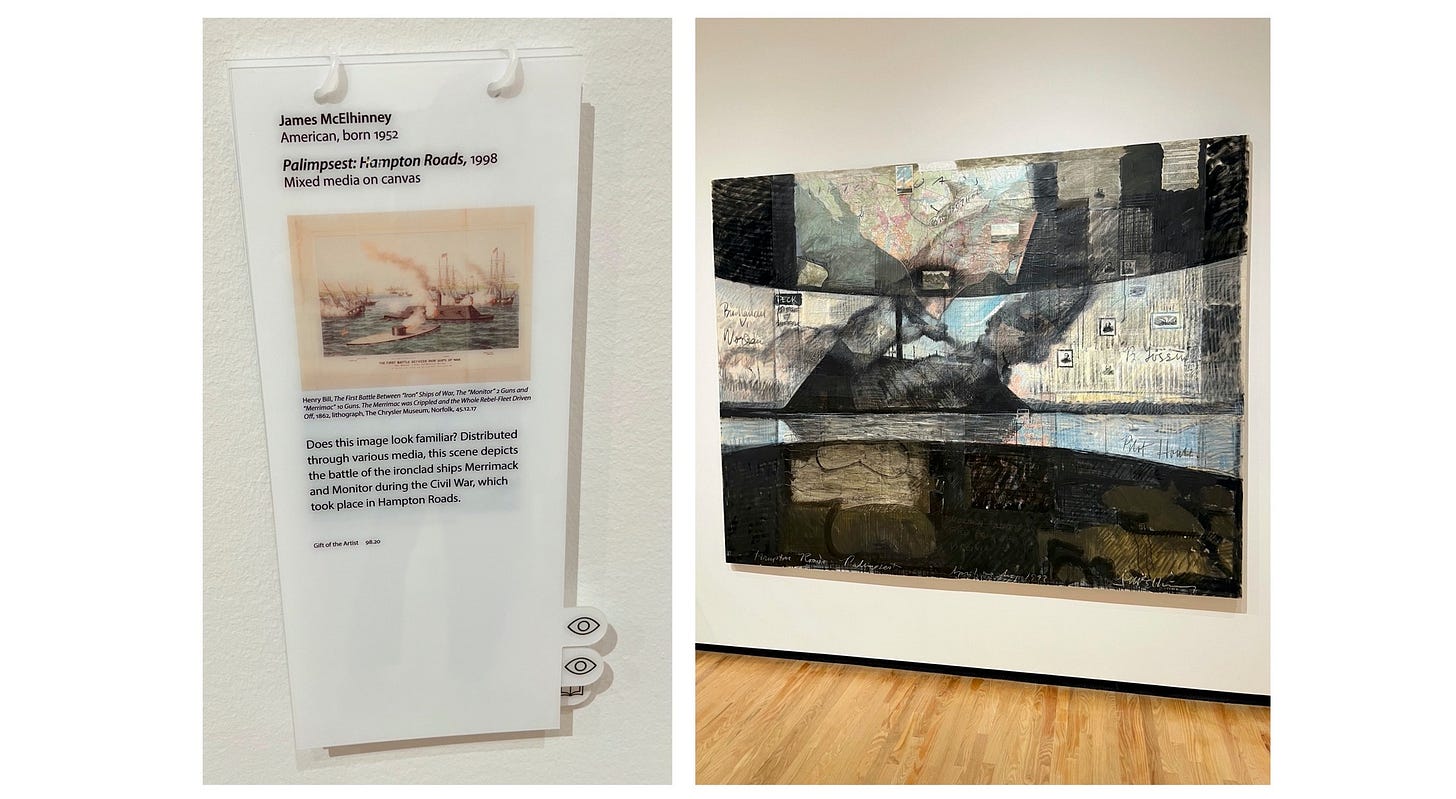

On March 15, 2024 the Chrysler Museum in Norfolk, Virginia will reopen its Modern and Contemporary galleries. One of the pieces to be included in the reinstallation is Hampton Roads Palimpsest; a large graphic painting with collage that was created in the museum courtyard. During the making of this piece, I interacted with school groups and visitors; to explain the nature of the process, and the thoughts behind it. The piece represented a departure for me, because of its being a maritime subject. The artwork represents an imagined view of the confederate ironclad Virginia, as it might have appeared on March 9, 1862, through a slit in the iron box that served as the pilot-house of the U.S.S. Monitor. Maps, architectural drawings, printed texts, portraits, and handwritten inscriptions constituted the image substrate, in an attempt to unpack a prismatic narrative of an historic event. While Akira Kurosawa’s 1950 film Rashomon had little influence the look of this piece, it was in the back of my mind as I sought to deliver a quasi-cinematic statement. In the words of writer Jim Waltzer,

“The artist James McElhinney has been expanding his “Hampton Roads Palimpsest” on site, adding journals, maps, sketches, and paintings to the 10-foot square document focusing on the Virginia-Monitor confrontation and nearby inland battles. This visual investigation explores changes in the harbor’s shorelines and waterways, providing a unique look at the impact of history and commercial development.”

(—Jim Waltzer. “Capturing the Battlefield: What a difference a century makes when artists confront Civil War sites.” Art & Antiques magazine. Summer, 1998)

Researching sites for my Civil War battlefield series required me to interact with public historians and park service rangers, who expanded my understanding of landscape as more than just a subject for painting. Richmond Battlefield superintendent Cynthia MacLeod introduced me to the writings of John Brinckerhoff Jackson (1909-1996), who wrote that “Landscapes make history visible.” To paraphrase Jackson further—landscapes do not occur in nature, but are created when people adapt terrain to their use. It would then follow that competing interests experience landscape in very different ways. For example, real estate developers see themselves repurposing idle lands for economic growth, while preservationists decry the development of hallowed ground as desecration. Caught in this tug-of-war, historic battlefields face uncertain fates, by erasure, revision, or preservation. The physical memories of a regrettable national past might thus be legible as a palimpsest; an overlay of competing systems of value, inscribed upon the terrain. To express this condition in visual terms, I combined elements of collage, painting, and graphic mark-making, by incorporating maps, pictures, and texts into the larger image. This provided me with a way to portray a singular location from multiple points of view.

The first of these palimpsests were produced between 1995 and 1998 were focused on a series of engagements fought during the federal army’s Neuse River raid, in December of 1862. Several of these Palimpsests were included in my solo exhibition at the Asheville Museum of Art in North Carolina, which acquired Foster’s Raid: Battle of Kinston Bridge for its permanent collection.

A selection of these artworks appeared in the June/July 1998 issue of New American Paintings: South #16, which was released around the same time the Chrysler Museum opened Sacred Sites: Then and Now: The American Civil War; an exhibition curated by Brooks Johnson that combined historic works mined from the museum’s collection, with loans from other institutions, and contemporary works loaned by the artists. This approach has been embraced today by numerous museums, but in 1998 it had yet to gain widespread traction. The idea of deconstructing the notion of modernity, or at least broadening its scope in this way, struck me as an exciting new way to approach historical storytelling. In the words of William Faulkner, “The past ain’t dead. It ain’t even past.”

In 1992, the Maryland Historical Society invited African-American artist Fred Wilson to use “. . . the museum’s collections to confront and challenge perceptions about history, culture and race.” “Mining the Museum,” proved to be a groundbreaking event. Similar tactics were employed by Philadelphia curator Julie Courtney for The Travels of William Bartram, Reconsidered; an installation by Mark Dion at Bartram’s Garden in 2010. Rosemary Trockel’s 2013 exhibition A Cosmos, at the New Museum in New York, and Barbara Bloom’s As it were, So to speak, at the Jewish Museum that same year reflected this trend. Rinehart’s Studio: Rough Stone to Living Marble at the Walters Art Gallery in Baltimore paired 19th-century statuary with contemporary works by sculptor Sebastian Martorano in 2015. Two years later, OVERLOOK: Teresita Fernandez Confronts Frederic Church at Olana reexamined “. . . Frederic Church and his contemporaries’ response to the cultures and landscapes experienced during their Latin American travels.” Jane Irish’s Antipodes—an installation at Philadelphia’s Lemon Hill Mansion in 2018—explored the impact of “. . .colonialism, opulence, the violence and futility of American conflicts overseas, and the anti-war activists who resist them. . .” In 2018, I collaborated with Independence Maritime Museum chief curator Craig Bruns to create On the Water: The Schuylkill River; a multi-media art experience incorporating both historic and contemporary artworks, as a pendant to the museum’s new River Alive galleries. Hudson River Museum chief curator Laura Vookles and I worked on a larger exhibition in 2019. “James McElhinney: Discovery the Hudson Anew” combined my recent works with historic books and prints “mined” from the museum collection. Deconstructing assumptions about contemporaneity appealed to me on a very basic level. I had always been suspicious of novelty, and dismayed by how the Industrial-era myth of progress had empowered rapacious manufacturing, the extractive practices that fueled it, and the environmental damage they caused. Progress could also be seen as an assault on memory, by diminishing the past as something with a sell-by date. Frederick Douglass had observed that the “. . . past is neither dead, nor indifferent.” The exhibition Sacred Sites: Civil War, Then and Now at the Chrysler Museum echoed a similar sentiment, in the summer of 1998.

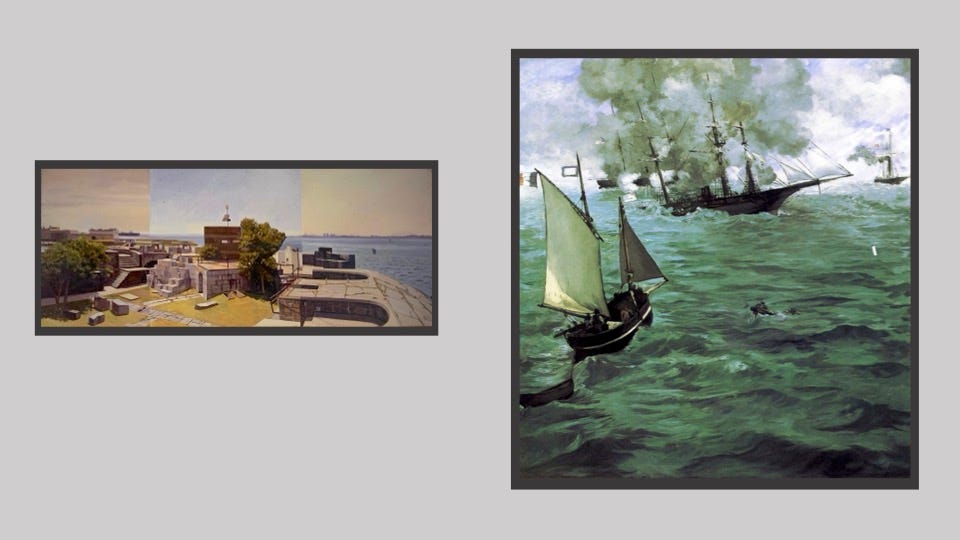

At the reception, I was stunned to find my 1993 painting Fort Wool, Hampton Roads beside Édouard Manet’s 1864 The Battle of the Kearsarge and Alabama. Pinhole photographs by my friend Willie Anne Wright were on view, next to Civil War Ambrotypes by Alexander Gardner. These experiences stirred somewhat puzzling emotions. Having been accustomed to looking at contemporary art and historic works as separate and different, the exhibition challenged visitors to look at both through a single lens. More than a century of changes collapsed into the moment at hand. Having grown up in the Delaware Valley, I was on intimate terms with Manet’s maritime painting in the Philadelphia Art Museum. In some ways, I knew it better than my own painting that hung beside it. Having now stumbled into what felt like a private conversation, I wondered what these two works might be saying to one other, and thought it best not to interrupt.