PRESSING MATTERS

#127: Whispering Life into The Machine

The house at number 4 Jodenbreestraat in Amsterdam is like hundreds of other dwellings built for wealthy merchants during the Dutch Golden Age, equipped with cocklofts for servants’ quarters and kitchens in cellars, where ceilings are nearly as low as between decks on Batavia merchantmen. The winding stair between floors have a maritime accent, with a railing of stout hempen rope. The home’s famous owner was not a tall man. In a basement room stands a peculiar contraption that might be mistaken for a medieval torture device. A frame-footed wooden table bisects a vertical cabinet housing a roller turned by large saltire-cross handles. Etchings hang drying on slender cables. A single window floods the space with raking. I was struck by its tidy economy. Not a square inch was wasted. This interior is in fact a curator’s vision of how Rembrandt’s printing shop might have looked had the artists just stepped out for lunch. I didn’t quite believe it. Rembrandt was financially feckless—an impulsive collector of random exotica from stuffed armadillos to Japanese swords. I imagined that the shop in his day would more closely resemble the Dublin’s Hugh Lane Gallery reconstruction of Francis Bacon’s studio—his window ledge workbench strewn with inky tarlatans, varnish pots, and other febrile detritus of his creative process.

I was recruited by Gerald Peters Galley in Santa Fe more than six years ago and needed a bridge between my sketchbook paintings and art made for walls. Mark Golden put me in touch with Golden Paints regional product rep Phil Garrett, who had recently moved to Santa Fe from the Carolina Piedmont. Phil put me in touch with master printer Michael Costello, with whom I produced a series of monoprints; essentially paintings on paper made on a roller press. I renewed my acquaintance with Philadelphia master printer Cindi Royce Ettinger, who helped me develop new intaglio prints. These collaborative experiences were electrifying. Adapting the Printmaking illuminated a conversation between drawing and color that was new to me. In the words of Henri Matisse,

"Si le dessin est de l'Esprit et la couleur des Sens, il faut dessiner d'abord, pour cultiver l'esprit et pouvoir conduire la couleur vers des chemins spirituels."

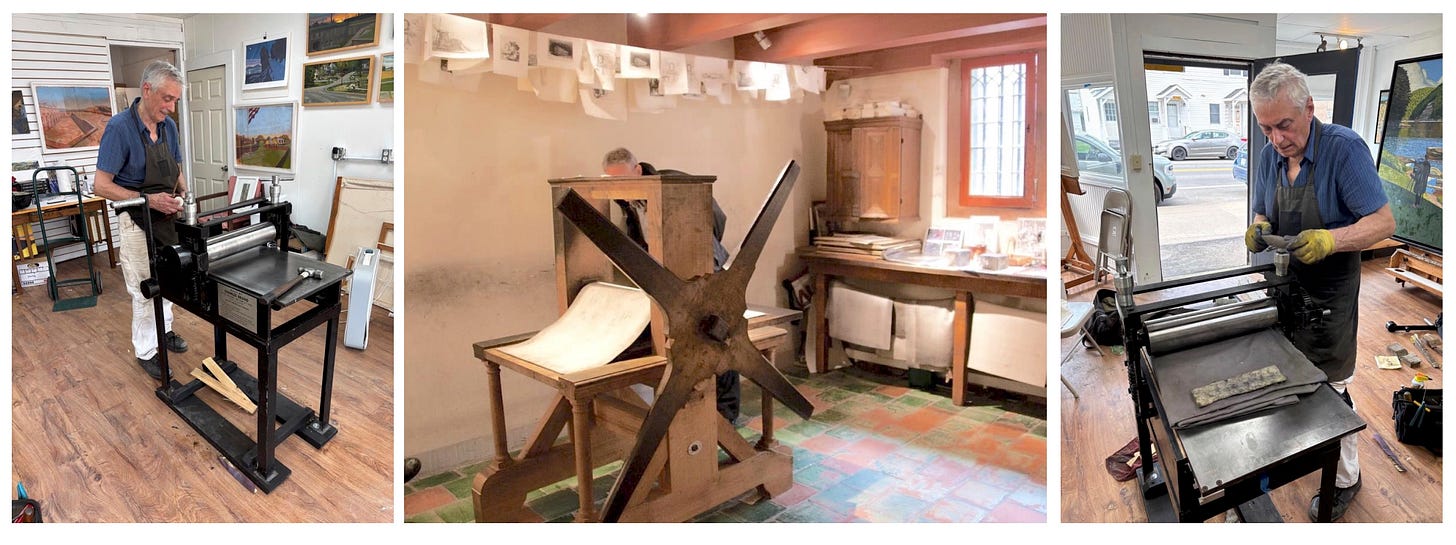

Between trips to Santa Fe, I visited a Yale classmate and his wife whose studios were in a renovated Hudson Valley barn. A small etching press stood in the corner of one of their large airy rooms. Paintings and drawings covered the walls, but no etchings that I can recall. Such a machine a century ago signaled cultural refinement, like a plaster casts of Michelangelo’s Écorché, or a piano in genteel parlors. I asked if they might be willing to part with it. Months later day the phone rang. My friends had decided to put their farm on the market and move to Manhattan. The press could be mine for a modest price. I leaped at the offer without pondering logistics of transporting nearly a quarter ton of steel 130 miles. The machine was dismantled. Its roller assembly was bundled in old towels. Bolts and random parts were packed in heavy-duty freezer bags. The stand, base, frame, and bed were manhandled into my vehicle’s cargo area, then driven to a self-storage lockup, where they gathered dust for two more years. The press moved again when I signed a lease on a storefront studio two miles from Rockwell Kent’s farm. I studied all its parts, reckoned how it might all fit together in an exploded view schematic, but resisted temptations to risk a reunion. I went instead in search of the nearest master printer.

The closest I found to the Adirondack region were Alain and Agathe Piroir in Montreal, and Ruth Fine at SUNY Plattsburgh, who referred me to Perry Tymeson—the owner of Suitcase Press—a company that refurbishes etching and lithography presses. A phone conversation with Perry revealed mutual connections, such as printmakers Cindi Ettinger, Roy Nydorf, and Evan Summer, who all held Perry in highest regard. His North Country tour had been scheduled for May. His bookings changed and the trip was postponed. May came and went, along with June and July. The peripatetic “Press Whisperer” finally made his appearance on August 14. The date was auspicious as my late parents’ wedding anniversary, and the birthdays of actor Steve Martin and filmregisseur Wim Wenders—both of whom were born on the very day Japan surrendered to The Allies in 1945.

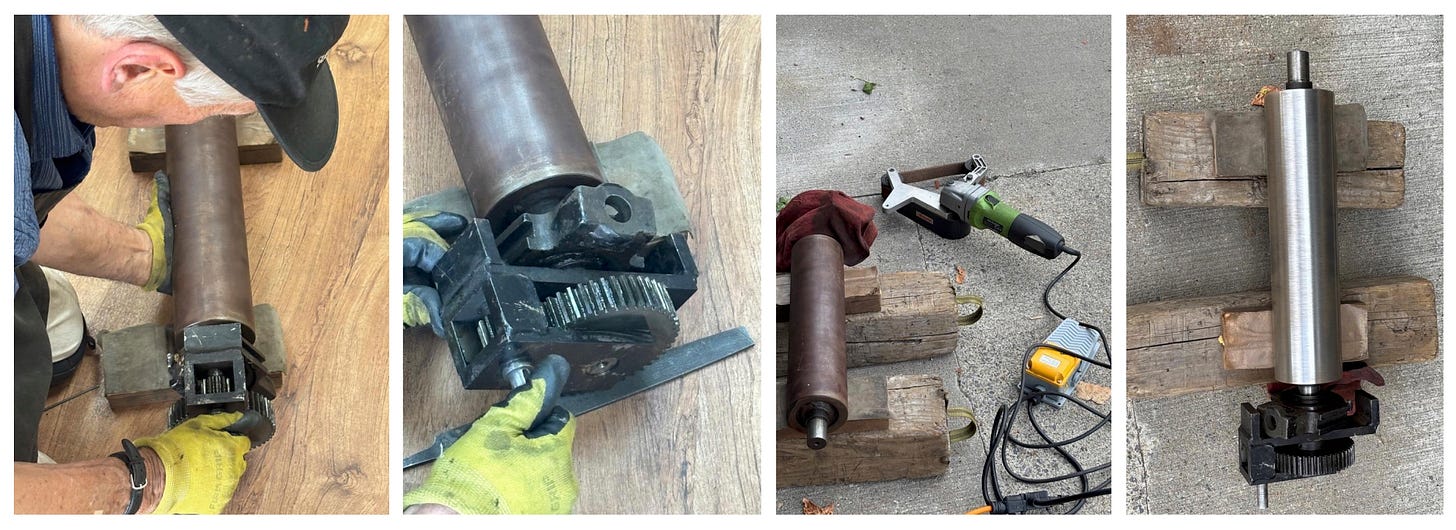

Perry inspected the press and dated to circa 1973. He explained that German-born engineer and inventor Charles Brand lived in The Bronx when patented new designs for etching and lithography presses in the mid-1960s and then set up shop in a basement at 84 East 10th Street in Manhattan a few years later. The address is printed on an aluminum plate screwed to one side of the base. The 1970s is regarded by some printmakers as the golden age of Brand presses, before the company shifted from innovation to production. Founded in 1956, Conrad Machine Company has been repairing Brand presses and in building new Brand-designed presses since the mid 1990s.

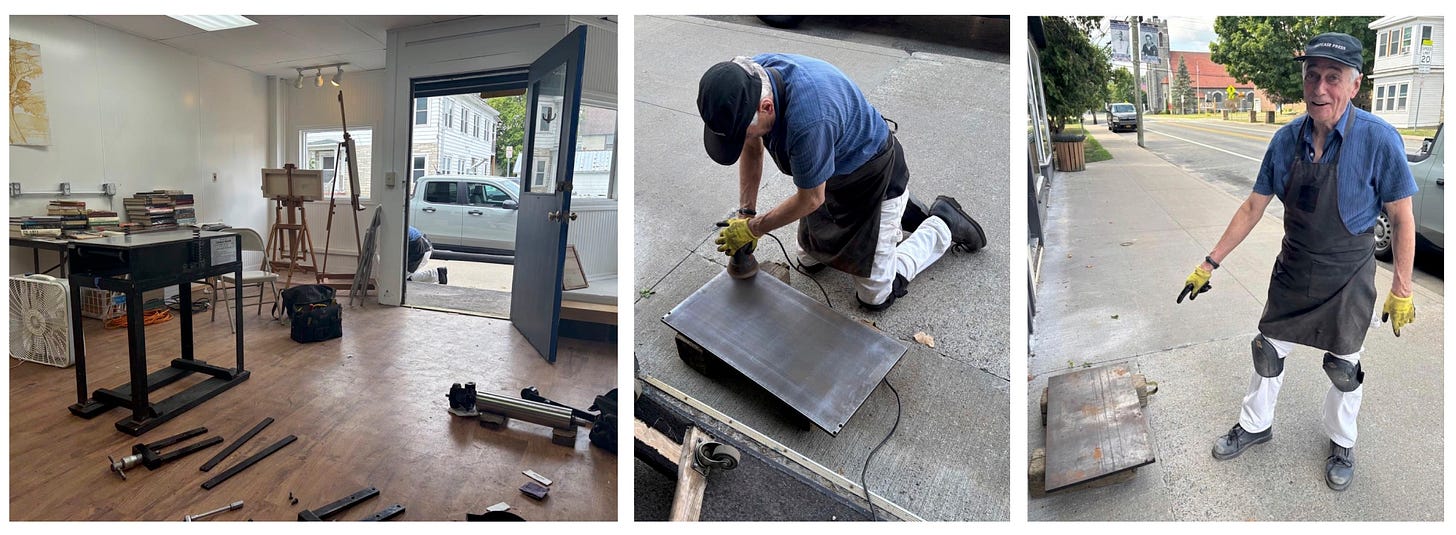

I could envision a schematic exploded-view drawing of the press but possessed no understanding of how it all went together, with out-of-the-way set-screw adjustments, grease ports, micro-gauge calibrations. The first step was cleaning the bed and the roller, which were coated in a brownish patina. Perry unscrewed the stops that keep the hundred-pound bed from rolling off its base. He explained that without these little bars the bed could come rolling off the base and onto one’s foot. He carried the steel slab out to the sidewalk, laid it on a pair of square timbers, and asked me to get a ruler. When he laid its edge against the bed, a tiny gap appeared. Press beds can distort with time and use. A sagging bed will provide inadequate roller pressure resistance to produce an even impression. Charles Brand knew this and made his press beds reversible. Perry ripped through the patina with a high-powered rotary sander and brought the roller back to bright metal with an abrasive-belted pipe-polisher. The cam assembly was dismantled, cleaned and greased. Parts of the metal upper frame that held the roller in pace needed to be stretched and reshaped to align with the bearing-blocks.

I became engrossed in Perry’s methodical process, as he reassembled the storied machine piece-by-piece. He ran an inkless plate twice through the press, packed up his gear and drove out of town. I sat there for a while, admiring the gleaming roller, spotless bed, undergirding, and black wooden sled that Perry had built. The sight inspired the gravitas of a Franz Kline painting, and a muscle-car yearning for an empty road. A dormant heap of steel had been transformed into something worthy of its name, in less than seven hours.

—James Lancel McElhinney © 2025

Thanks for visiting TRUE PLACE. Subscribe to receive more articles about travel, art, history, and the environment. Become a paid subscriber to access 126 previous dispatches.