Journal Entry: January 2, 2000. Summit Springs, Akron, Colorado. 40.4336 x -103.1401

Ninety minutes after leaving Denver, I stop in Fort Morgan to buy fuel and ask for directions. The mechanic pumping gas at the Texaco station warned me that driving to Wray—and nearby Beecher’s Island battlefield—would be another 90 miles further to the east, and that raveling such a distance in the dead of winter might demand a more serious vehicle than my fishtailing sandbagged rear-wheel-drive six-cylinder Leonard-capped Ford Ranger. I made it a habit of never venturing into the Rockies or onto the plains without an emergency supply of energy bars and water, a couple of Mylar survival blankets, an army surplus folding spade, some road flares, and a .357 revolver, loaded with alternating rounds of snake-shot and hollow-point bullets. My first cell-phone purchase was almost a year in the future. GPS was unavailable for civilian use. The attendant warned me to be on the lookout for police.

“It’s a hell of a dull trip along here. Cops get plenty bored. They might just stop you to have someone to talk to. I got pulled over, once driving a truck that couldn’t go 60. Speed limit out here is 65.”

He told me that his brother got stopped for a broken tail-light on the road to Wray, and an open warrant on some minor offense landed him in the calaboose. The moral of these stories, I suppose, was that getting to Beecher’s Island would require a full day of cop-dodging mind-numbing travel in a four-wheel drive vehicle. That was the gist of it. Armed with this new intel, I decided to scrap my plans to proceed further, and returned instead to Tall Bull’s last stand.

Taking the off-ramp for Atwood, I head southeast on state highways 63. The high plains roll out before me. Tumbleweeds cluster against wire fences. A jackrabbit dashed across the unpaved road, fifty yards ahead. Beneath a golden sky, the saw-tooth skyline of the azure Rockies disappeared from my rearview, as I press deeper into the prairie. After traveling for five miles, I turned left onto county road number 2. Many of the secondary roads in this part of the country follow a network of township-and-range survey lines, that seen from the air resembles a checkerboard. Traveling across such terrain combines mind-numbing straightaways with 90-degree turns that can make inexperienced motorists feel like Pac-Man contestants. After heading due east for four miles, the road suddenly turned north, but I continue east on an unimproved extension of the road I had just been on. Please bear in mind that there I had no cellphone. The sun would set less than two hours later. I was rolling the dice on whether my truck would be equal to unknown road conditions; equipped with a handgun, a box of ammunition, two Mylar blankets, some bottled water and a box of energy bars stowed behind the driver’s seat. I decided to take my chances. After a bumpy ride on packed dirt and loose gravel, the road turned south. Driving downward over low bluffs, I descend to the outflow of a nearby stock-pond that cuts through grassy bottomlands.

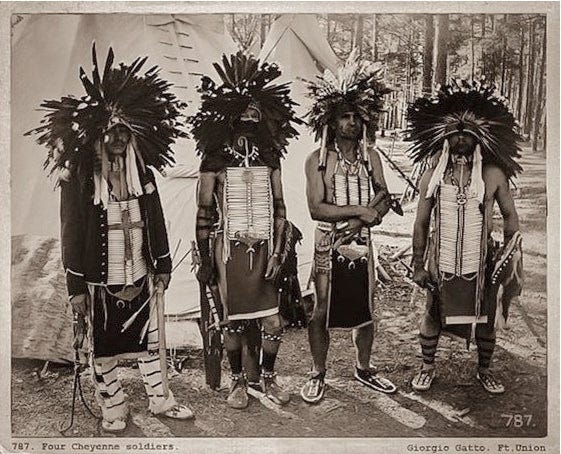

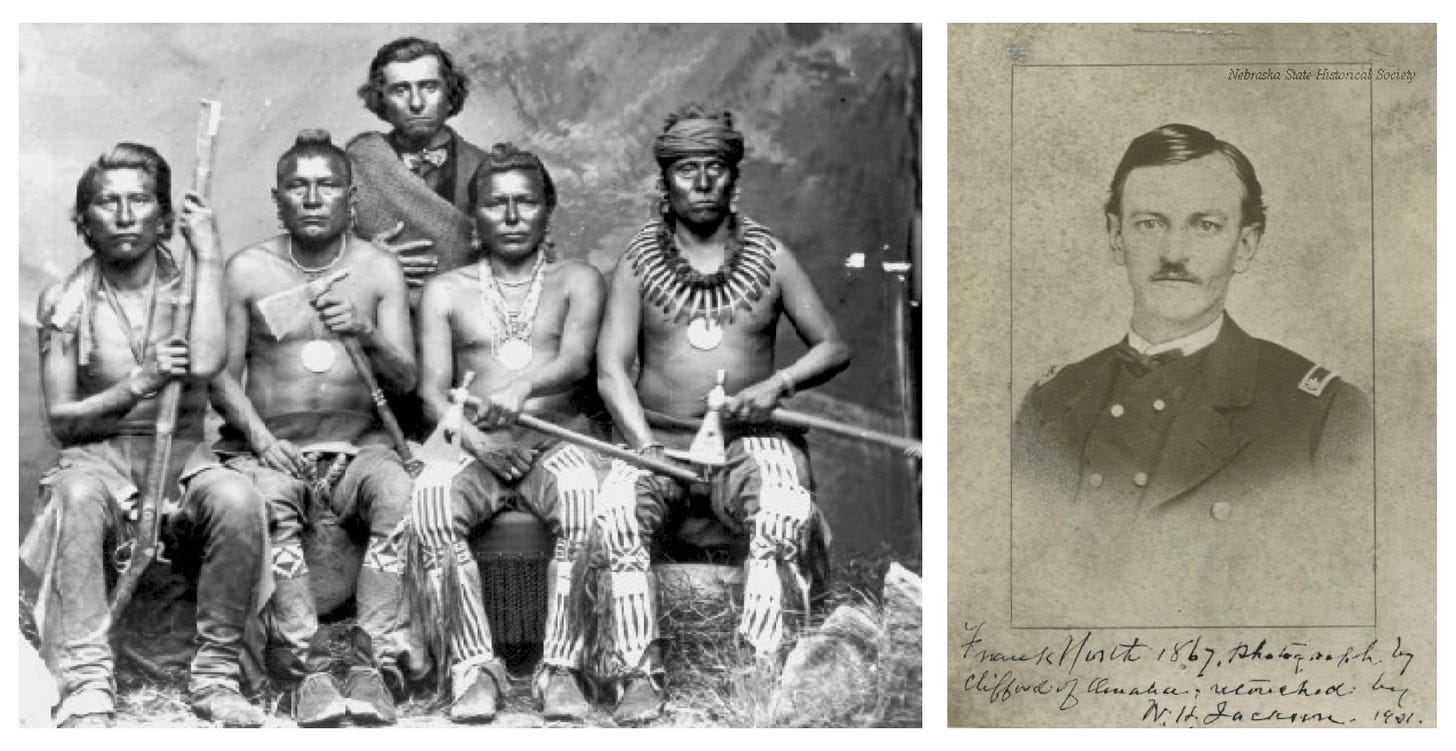

Hotóa'ôxháa'êstaestse, also known as Tall Bull, was a Cheyenne war chief and leader of the elite Hotamétaneo'o warrior-society, also known as Dog Soldiers; fighters who would go in battle, tethered to a sacred arrow thrust into the ground. Tall Bull and his militant followers opposed Black Kettle’s conciliatory attitude toward the U.S government, in favor of violent resistance. The massacre at Sand Creek led many Cheyenne exact bloody vengeance from settlers, soldiers, and random travelers, who might happen to cross their path. While the Cheyenne and Lakota fought the U.S. Army, they were also at war with other indigenous nations; such as the Crow, Arikara, and Pawnee, whose warriors sometimes fought alongside the blue-jacketed federal troops. Following their military service in the Civil War, Frank and Luther North led a battalion of Pawnee Scouts in a number of campaigns between 1865 and 1877. The Pawnee Battalion was attached to the command of U.S. Army colonel Colonel Eugene Carr, when they came upon the Dog Soldiers’ camp on July 11, 1869. When the smoke had cleared, both Tall Bull and his wife lay dead, along with fifty other persons; both civilians and combatants.

I arrived at Summit Springs, around 3:30 in the afternoon. A leaden cloud-wall rolled in from the southwest, beneath a blazing sun. Descending a narrower byway, I plunged down the bluffs to grassy flatlands beside a stream. The road terminates at a muddy loop, around which small monuments have been placed. Stepping out of the vehicle I notice a few clumps of brown fur on a patch of earth, stained with about as much blood as might be shed by a rabbit. Strewn about were more bits of the same brown fur—scraps of a savage feast for coyotes, or ravenous raptors. Across the narrow creek the land rises to a gentle knoll, scored by deep gullies with sheer, muddy walls. I work in haste as storm-clouds approach, alternately drawing in my sketchbook and taking photographs. A previous visitor had placed the leg bone of a slightly larger mammal—perhaps a dog or coyote—atop Susanna Alderdice’s cenotaph. A new Lincoln penny lay on a ledge of the battle monument that had been dedicated in 1909, to mark the fortieth anniversary of the fight. Luther North attended the ceremony. His famous older brother had passed away in 1885, from injuries sustained in an equestrian accident. Following his retirement from the army in 1977, Major Frank North ran a cattle business with William F. Cody, and traveled with Buffalo Bill’s Congress of Rough Riders. Luther survived him by forty years. Their story, and that of their indigenous comrades-in-arms, were chronicled by George Bird Grinnell (1849-1938) in Two Great Scouts and Their Pawnee Battalion. The book has been reprinted many times since its publication in 1928.

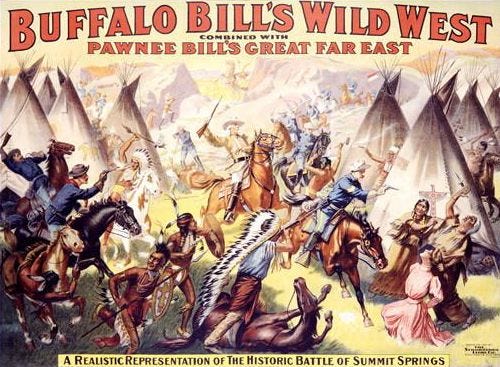

The battle of Summit Springs was re-enacted many times in Buffalo Bill’s “Wild West” show, with Cody galloping to the aid of two captive white women, too late to save one of them from being tomahawked by Tall Bull’s wife, whom Buffalo Bill dispatches with a six-shooter, freeing the German beauty from the clutches of her assailant. What probably happened during the panic and confusion ensuing from Carr’s surprise attack, was that Maria Weichel and Susanna Alderdice were set upon by their captors.. Alderdice took a first bullet in the skull, and then a tomahawk blow to the head. Weichel fought back, tried to escape, and was shot in the back, just as Cody felled her assailant, or so he claimed. By all accounts, Maria Weichel was extraordinarily attractive, and no less resilient. The trauma of her captivity did not prevent Weichel from finding a husband, and getting on with her life. Tall Bull may have been killed by Frank North, or by cavalryman Daniel McGrath, but most are willing to let Cody take the credit. History buffs may debate the veracity of either claim, but Carleton Young’s memorable line from John Ford’s classic film, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance sums it up. “When the legend become fact, print the legend”

Unlike Cody, the North brothers today have faded from memory. One of the most touching battle markers I have ever visited on any battlefield is a standing slab of rough-cut stone honoring the Cheyenne boy who was shot down, after he drove the pony-herd to safety. Pebbles, medicine-bundles, and dried flowers lay scattered around its base. In his memoir Man of the Plains, Luther North describes the uncommon valor of the unnamed teenager.

“About a half mile from and off to one side from our line, a Cheyenne boy was herding horses. He was about fifteen years old and we were very close to him before he saw us. He jumped on his horse and gathered up his herd and drove them into the village ahead of our men, who were shooting at him. He was mounted on a very good horse and could easily have gotten away if he had left his herd, but he took them all in ahead of him, then at the edge of the village he turned and joined a band of warriors that were trying to hold us back, while the women and children were getting away, and there he died like a warrior. No braver man ever existed than that 15 year old boy.”

The smooth pebbles balanced on its flat upper edge remind me of visiting-stones on Jewish graves and Irish headstones. On October 7, 1780, a force of back-country American militia attacked a detachment of British and Loyalist troops at Kings, Mountain North Carolina. During the battle, Major Patrick Ferguson was shot dead from his horse, and hastily buried by his victorious slayers. As the rocky soil would not admit a proper grave to be dug, the body was covered with stones. It is customary for visitors to add stones to the Scotsman’s cairn. This tradition seems to traverse cultural boundaries. One of the famous landmarks of Ireland is Cnoc na Riabh, a neolithic mound reputed to be the final resting-place of Queen Medb of Connaught. The large cairn crowns a ribbed hill, on the Atlantic coast of Sligo. Leaving a stone may bring good luck, but removing one risks being cursed. Archaeologists have never dared to excavate the monument.

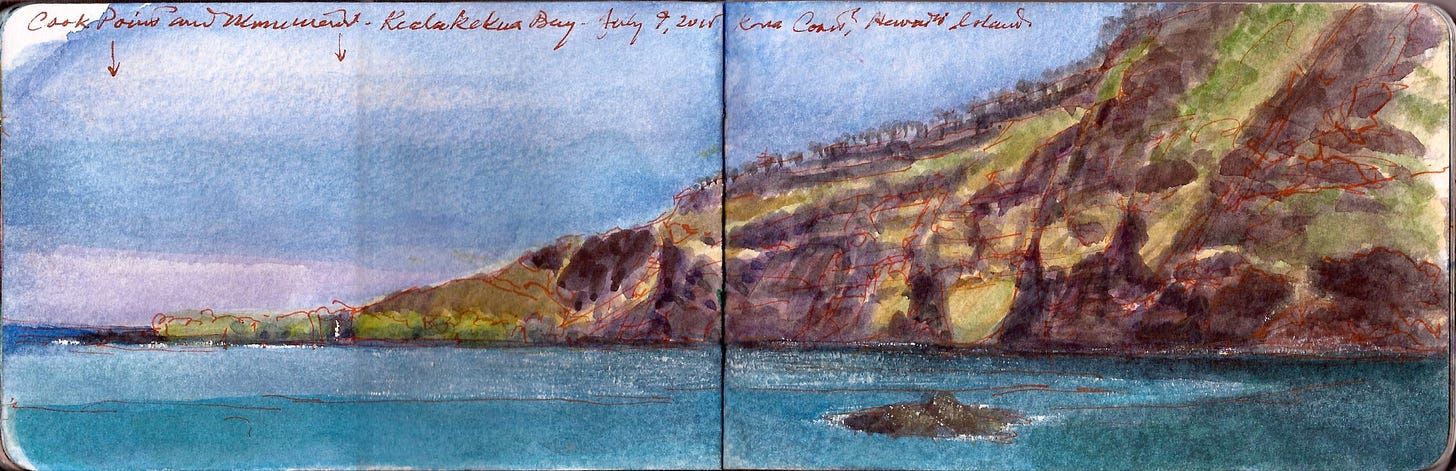

I encountered similar traditions on the island of Hawai’i. Leis had been presented to me as greeting-gifts and marks of respect. Discovering that they never would be allowed to return with me to the mainland, I drove to the end of Puuhonau Road, to cast them into Kealakekua Bay. Standing near a small heiau, two indigenous men were hawking unlicensed snorkel-tours. The younger man had a stunning physique, his torso covered with traditional tattoos. Explaining my dilemma to them, the young man replied to me,

“These leis were made with love, and given to you with respect. They’re yours. It’s a bummer you can’t take them home with you. I appreciate that you don’t want to put them in the garbage. Go ahead and lay them on the water. That’s cool. But whatever you do, don’t take anything from the island, not even a shell, a rock or a pebble. They belong to the sea and the land. We have to respect that.”

Setting up next to the battle-monument, I take notes and make sketches. A large SUV arrives. Three white males emerge, dressed in blaze-orange ball-caps and vests. Drawing their weapons from soft cases, they nod to me politely, scramble over the wire-fence and march off to a pond half a mile away. Working on a small oil-study, I hear the distant bark of shotguns. An hour later the hunters return, each with a couple of canvasback ducks. The depart. I linger awhile. After five o’clock the light fades. The mercury plunges sharply. Purple shadows flood the broad hollows between prairie-swales brushed with golden light. A sudden ray bursts throught the clouds to reveal Tall Bull’s last refuge; its jagged gashes, ripped into the prairie. Lifting the small painting from the easel, I set the panel inside the upturned lid of a cardboard banker-box that serves as my drying-tray. Wiping my brushes, I scrape the palette, pack my weatherbeaten French easel, and secure it all with bungee cords, before sliding it onto the bed of my pickup. Climbing into the cab, I take a swig of cold coffee, fasten the seatbelt, light a cigar and throw the truck into gear. Loading the Chieftains’ The Long Black Veil into the cassette-player, I hear the plaintive opening chords of “The White Cockade,” performed by Sting.

Sé mo laoch mo ghile mear

Sé mo Shéasar, gile mear

Suan gan séan ní bhfuair mé féin

Ó chuaigh I gcéin mo ghile mear

A bold and gallant chevalier

A high-born scion of gentle mein

A fiery blade engaged to lead

He’ll break the bravest in the field”

Driving up and away from the muddy turnaround feels like escaping a tomb, just as the departed are gathering. In the raking sunlight, luminous dust-clouds chase me, glowing like afterburners. Stretching out across the plain from both sides of the road, the shorn fields’ blazing bronze cools to rusty hues. Yet another daredevil jackrabbit sprints across the road. Thunderheads roll east toward Kansas, to upend trailer-parks, or launch farm-girls to Munchkinland. Along the southwestern horizon, the twin summits of Long’s Peak soar above the shadowed plain. Sunbeams pierce the faraway clouds, as those overhead race eastward, to reveal thousands upon thousands of points of light in a rapidly darkening sky. Low in the distant sky there arises the mercury-vaporous luminiescence of a sprawling metropolis, as night falls over central Colorado. Southbound from Fort Morgan on Interstate 76, the traffic increases on the approach into Denver. The occasional truck-stop, mini-marts, or ranch gives way to housing developments, industrial parks, and the sprawling fringe of suburbia. Driving into Denver that night felt like flying a starship into the bright heart of a galaxy. Retreating from the umbrageous desolation of what explorer Stephen H. Long drescibed as the “Great American Desert,” I am subsumed by a haunting sense of absence—of things missed, forgotten, or left behind. No one resides at Summit Springs, but troubled spirits abide

FOLLOW The Sketchbook Traveler on Facebook, Linkedin, Twitter and Instagram.

Now available: SKETCHBOOK TRAVELER: Special Offer from Ecoartspace.org: All three volumes for $45.00 (a savings of $29.85) ORDER HERE