Journal Entry: Monday, August 09, 2010

“I just completed a 40 x 40-inch painting of Constitution Marsh and the Hudson Highlands, as seen from the “Belvedere” at Boscobel House and Gardens in Garrison, New York. The composition was inspired by a series of journal-painting I had made on the spot, but the painting was done entirely from memory. This is my first major effort at working in acrylic—a medium held in contempt by some traditional oil-painters as the preferred medium of color-field abstractionists.”

French academic painter Jean-Auguste Dominique Ingres is quoted as saying that “Le desssin est la probité de l’art.” Who could disagree? Works of art created without a solid foundation in drawing can rely too much on parlor tricks and facile effects to be taken as sincere. CGI and AI give image-makers shortcuts to quick results today, but there are as many reasons not to rely on these technologies. At the opening of the Hamilton Wing of the Denver Art Museum in 2006, I asked starchitect Daniel Liebskind about his design process. He replied that broad concepts took shape in hand-drawn sketches, which then were translated into workable plans. “Do your designers work in AutoCAD?” I asked him. “No, “he replied. “We have technicians for that.” Liebskind described how concepts were fleshed out by a design team in a variety of media from graphite to markers. This struck me as similar to the round-robin drawing sessions employed by Disney, SONY Pictures Imageworks, other animation studios. An article I wrote in 2006 for American Arts Quarterly compared a display of historic drawing manuals at the Grolier Club with the Pixar exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. As part of my research for the piece I met with Ray Allen—Dean of the Maryland Institute College of Art, who underscored the centrality of life drawing to the school’s animation and game design programs. This sentiment was echoed by Sid Meier, whose game-design company Firaxis employed a number of MICA graduates. “If you want to become a designer,” I was told, “You’ve got to know how to draw.”

While digital media created new ways for people to make art, the primacy of drawing remained unchanged. In light of this fact, shifting one’s practice from one analog painting medium to another would be a minor adjustment. Reproducing the effects of oil painting was frustrating, until I realized that mimicry was pointless. Great progress has been made in the development of products such as Golden Paints “open” acrylics and water-miscible oil paints produced by other manufacturers. One had fewer options twenty years ago. I knew many oil painters at the time who had dabbled in acrylics once or twice, and then quit in disgust. I was one of them. What I learned from working with acrylics was that few of my peers knew how to paint properly in oils. Many of the painters that were trained after 1945 were taught to swish, dip, and smear; mixing colors on the palette, after wetting the brush with solvents. Technique was of secondary concern, when compared to personal expression. I am reminded of how little emphasis was placed on the traditional craft of painting whenever I look at the arid, brittle surfaces of some of my early attempts at painting. Things are different today. Much of this forgotten knowledge has been rediscovered by the recent realist revival, and promoted by the Atelier movement.

In the early 1970s, John Moore at Tyler, and Arthur da Costa at Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts had each interacted with Dick Fitch of Turco Paints, to develop and test an alkyd-based megilp concocted to simulate the Black Oil painting medium developed by the Louvre’s technical director Jacques Maroger (1884-1962). Fitch’s son Robert also studied at Tyler. Through him I arranged to meet his dad at Turco’s rambling 19th-century building near the Philadelphia waterfront. The chemistry may have been over my head, but it was deeply satisfying to learn about the world of paints and stains, pigments and siccatives. Turco Classic painting medium became a cult favorite until its patent expired and it was reborn as Liquin, Galkyd, and other Alkyd mediums.

Richard Callner, Roger Anliker, and Jules Kirschenbaum were among the few other faculty members at Tyler who promoted the knowledge of traditional techniques. While many of our classmates were aping the latest trends in the New York galleries, Callner had us reading Cennino Cennini, and looking at Vermeer. We learned about egg tempera, and how to make rabbit-skin glue as a sizing for oil-primed canvases.

“Rent a chateau in the Loire Valley,” Callner advised his students. “Hire a local gamekeeper. Shoot a fine, fat cottontail with your bespoke Holland & Holland side-by-side shotgun. Only the best will do! Remove the pelt and have the cook prepare Lapin Chasseur. Tack the elastic inner skin to a board, then let it dry. It will soon become brittle. Break it up. Wrap the pieces in an Irish linen handkerchief and beat it into smaller pieces with an oak mallet. Place the pulverized rabbit skin into a tin-lined copper Bain-Marie, filled with spring water, at a ratio of 14 to one. Melt the skin on medium heat. Keep an eye on it! Boiling would render it useless. Once it dissolves, remove the pot from the heat and wait for the mixture to cool just enough to dip a finger into it. Gently touch the surface with the tip of your index finger. Now tap it against your thumb twelve times. When your fingers stick together on the twelfth tap, the glue is ready to apply. Do it quickly; before the liquid cools. If it becomes too gelatinous, it will make the canvas brittle.”

Whether or not one regards painting as alchemy, the backstory Callner unpacked for us was more entertaining than a subway ride to Utrecht Paints, to buy a gallon of acrylic gesso.

Australian artist Ermes de Zan was in the graduating class at Yale, one year ahead of me. He was among a small number of students that were interested in classical painting techniques. For his thesis-show chef d’oeuvre, Ermes built the most beautiful stretcher any of us had seen. I recall that it was fashioned from Philippine mahogany, or perhaps California redwood, and assembled like a piece of fine cabinetry. Ermes had sourced the finest Belgian linen, to serve as the painting’s substrate, which he stretched as tight as a drumhead. The big day arrived when Ermes sized his canvas with rabbit skin glue, which might have been French, or perhaps from a Tuscan coniglio. There could be no doubt that it was of the highest quality that money could buy. Ermes’s vast empty canvas was by itself a thing of beauty which, in its pristine unprimed state, could have been mistaken for a minimalist masterpiece.

Gray linen glistened under a warm film of peau de lapin, as Ermes laid down the last strokes, left the studio and went to lunch. Later that afternoon, tortured screams pierced the air, like heretics ablaze, followed by a torrent of blue invectives. Those within earshot rushed to Ermes’s studio and beheld his magnificent stretcher splintered and warped; its upturned corners suspending opposite corners of a bent linen plane. Perhaps he had neglected to pre-wash the linen, or applied the glue before it had cooled, as the linen shrunk with such terrible force that it cracked and distorted the frame.

Bernard Chaet was a fount of ancient technical knowledge at Yale. His Boston classmate Reed Kay had just published The Painter’s Guide to Studio Methods and Materials. Chaet published An Artist’s Notebook seven years later. I and several of my classmates appear in Bernie’s book—grinding paint by hand with glass mullers. Those students who cared about the craft of painting learned about meglips; “fat over lean,” grisaille, imprimature, and camaieuunderpainting, glazing with complementary colors. We learned about color theory versus pigment practice, and the safe use of hazardous pigments such as cadmium and lead. Acrylic was still in its infancy, and therefore received little attention.

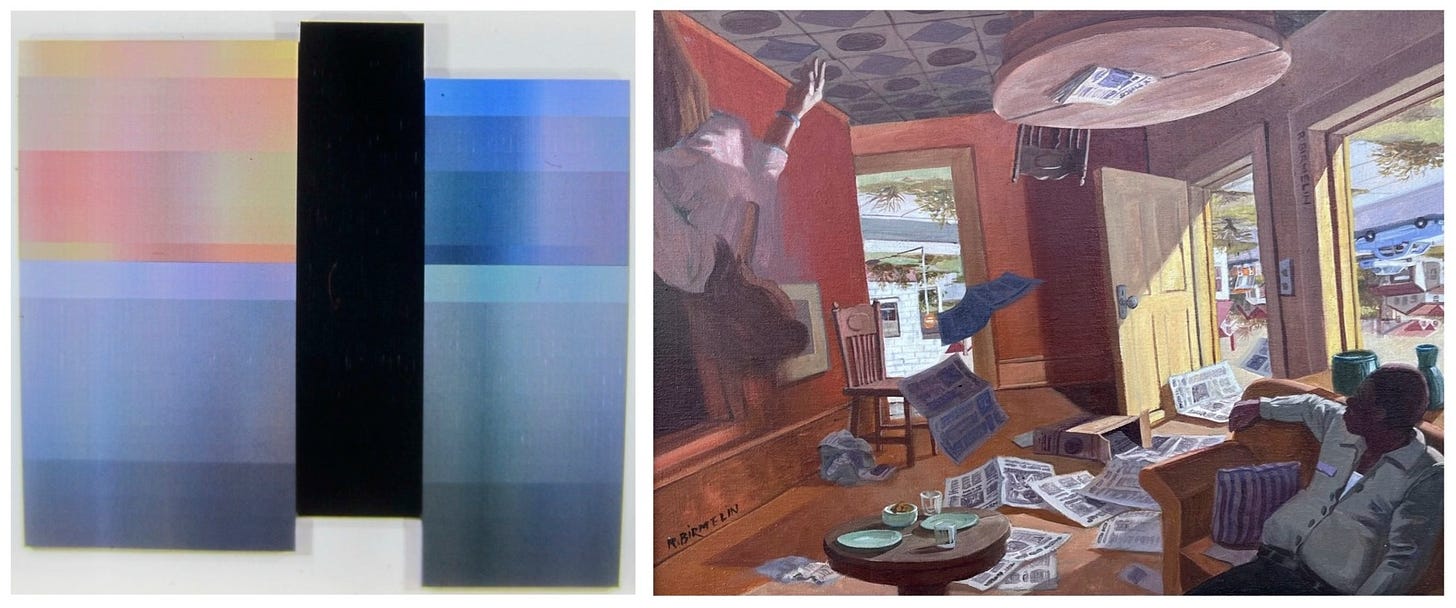

Two of my professors at Tyler School of Art had been vocal exponents of acrylic paints. Yale MFA graduate Frank Bramblett worked with Rhoplex; the raw polymer emulsion that serves as the binder for acrylic artists’ colors, while Richard Cramer’s precise geometric abstractions evoked the movement of light. Frank was more doctrinaire in his teaching about the moral imperatives of progressive modernism, whereas Cramer led students in outdoor painting sessions to experience firsthand the phenomenon of light. The color-theories of Albers, Itten, Ostwald, Chevreul and Goethe were discussed to such a degree that Cramer was given the sobriquet Captain Color. His painting method consisted of filling a vast grid with thousands of color-swatches that together made smooth transitions across the painted surface. The ingredients for each swatch were measured out with plastic syringes onto a plate-glass tabletop; then mixed with a palette-knife and stored in small jars. I was one of the student assistants whom Cramer employed at his 10th Street loft, for which one received modest pay, plenty of beer, and meals prepared by his lovely wife Carol.

This experience served me well, when more than thirty years later I was forced to abandon oil paint, in favor of aqueous media. Around Halloween of 2005, I caught a cold that worsened to what appeared to be severe bronchitis. On Veterans Day Kathie called a town car and delivered me to the ER at Columbia Presbyterian Hospital. I waited on a gurney for most of a day before being put in isolation room. Doctors declared that my hopes of survival were slim. They were clearly alarmed by my symptoms, and equally mystified as to what caused them. In hindsight, it may have been a then undiagnosable strain of SARS. Following my discharge from the hospital more than three weeks later, I found exposure to spirit vapors and even the odor of oil paint most disagreeable. With some reluctance, I began to explore watercolors and acrylics.

Robert Birmelin is a painter whom I long admired. Bob had shifted his practice from oils to acrylics many years prior. His studio was for many years located above an Irish pub on West 14th Street. During occasional visits I took note of how he laid out his palette, and kept the quick-drying paint pliable and moist with Saran wrap, spray bottles and plastic ice-cube trays. While acrylics had been promoted as a medium of modernity, Bob’s approach to painting might be compared to Van Eyck, who built up glazes over detailed drawings, or Tintoretto, Rubens, and Delacroix, who drew directly with paint. Like mixing color-swatches in Dick Cramer’s studio, watching Birmelin coax paintings out of drawings had prepared me to make the leap.

(To be continued)

—James Lancel McElhinney © 2024

The Holidays are coming: Three books for less than the price of two: CLICK on the image below—

Wonderful painting, James. As my studio is “home”, I have switched to water soluble oils, in particular, Holbein. No toxicity, beautiful colors, well pigmented.