The Man From Nuremberg

Sketchbook Traveler Albrecht Dürer (7-minute read)

CHOROGRAPHY (kəˈrɑgrəfi) = The art of describing regions and places

Thanks for reading SKETCHBOOK SOJOURNS! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

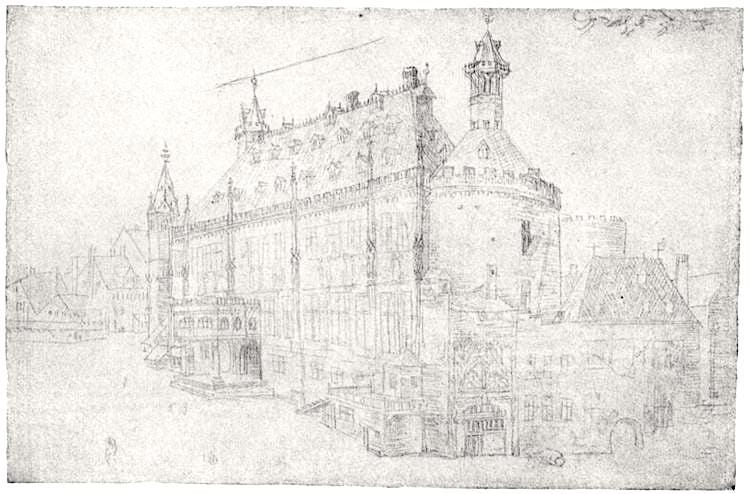

Diarist and painter Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) recorded his 1494-95 travels in watercolors of alpine scenes and views of Italy, many of which survive today. Dürer was not unique in this practice. Few of his contemporaries traveled so much as he, nor took similar pains to preserve their sketchbooks and journals. Leonard da Vinci (1452-1519). In 1520, Dürer journeyed from Nuremberg to Aachen, to attend the imperial coronation of the new Holy Roman emperor Charles V, whom Dürer hoped would renew the pension granted to him by the late Maximilian I, and to land a few portrait commissions to pay for the trip. He bundled up his long-suffering (or insufferable) wife Agnes, a maid, and a cargo of prints he hope to sell along the way. Traveling through The Netherlands, Dürer filled a silverpoint sketchbook with drawings of landscapes, animals, buildings, and human beings. Only one sketchbook from the trip is known to exist. There may have been more, but none so far have come to light.

Readers may be unfamiliar with the drawing technique known as silverpoint. A coating of opaque white watercolor is first thinly applied to a sheet of paper. Dürer would have used Flake White (Lead Carbonate) as the pigment. Drawing on this surface with a silver needle produces a linear effect similar to graphite. What happens is when silver touches lead, a chemical reaction leaves faint marks on the page. These slowly darken as the silver residue tarnishes.

Graphite (1.CB. O5a) is a naturally-occurring crystalline form of Carbon harvested by mining. Prior to the 19th century it was widely used as an industrial lubricant. Joseph Dixon (1799-1869) discovered the mineral’s potential as a writing material, by inventing a way of enclosing a thin graphite rod within a Cedar wood holder. He first manufactured these pencils in 1829. When Civil War soldiers, special artists, and journalists clamored for dry, portable alternatives to pen and ink three decades later, Dixon increased production. His famous Ticonderoga pencils are still in use today. Like silverpoint in Dürer’s day, Dixon’s development of the graphite pencil was motivated by a strong demand from people on the move.

Schoolchildren in the early 19th century first learned to print with chalk on slate, before advancing to cursive penmanship with ink on paper. Dixon’s cedar wood pencils changed all that. His first attempt to market his invention coincided with the so-called Art Crusade, led by artist-educators such as Rembrandt Peale and John Gadsby Chapman. Horace Mann described drawing as “an essential industrial skill” that improved penmanship. Let’s imagine that Dürer had misplaced his silver stylus. He could easily have replaced it with a brooch-pin. Four centuries later, the world needed a cheap disposable writing device that could be carried in explorers’ musettes, students’ rucksacks, or golfers’ pockets. Dixon’s graphite pencil met all those requirements.

Watercolor is likewise well-suited to travel. Colors can be transported in dry form; to be activated by water into a quick-drying paint. The watercolors Dürer would have carried on his travels consisted of rock-hard cakes that could be liquefied when rubbed against an ink-stone holding a few drops of water. This laborious process was the same used for hundreds of years by the countless book illuminators whom Herr Gutenberg had put out of business. As printed editions replaced handmade book plates, woodcuts and later intaglio engravings were embellished with watercolors. It was the ideal medium for an age of exploration, In which cartographers, naturalists, and topographical artists, enriched their journals with visual data.

Grand Tour diaries emulated these expeditionary notebooks. Not until late 18th century did someone invent soft cake watercolors that could be liquefied with the touch of a wet brush. By mixing simple syrup with Gun Arabic in the paint-grinding process, a more malleable substance was produced. In the 1830s, William Windsor and Henry Newton discovered that by replacing sugar-water with glycerin, they would be able to manufacture watercolors on an industrial scale. At the height of the Industrial Revolution, steamboats and railroads expanded the range of traveler artists such as J.W.M. Turner, for whom watercolor was an indispensable companion.

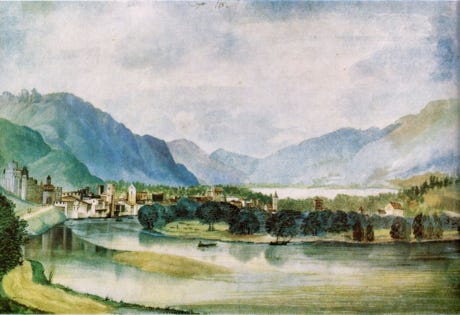

Much of Durer’s travels in 1494 would have been on foot. Any young man would have preferred his own legs to the confines of crowed carriages. By modern standards, traveling on horseback would have been done at a leisurely pace. A horse can walk about twenty percent faster than a human being, but not so quickly that a rider would not notice little things along the roadside, while drinking in a stunning vista. Durer’s view of Trento on the Adige River is like a modern travel poster. From a bankside road, beside tranquil waters, we behold an orderly townscape. Tiny figures approach the city gate on foot. Rising up behind the town are the soaring heights of the Dolomiti Alps, rendered with topographical specificity.

By a strange twist of fate in 2002, I represented the State of Colorado at the ceremonial signing of a sister city agreement between Trento and Colorado Springs. What appears to be a distant lake in Dürer’s watercolor does not in fact exist. The nearest large body of water—such as that which appears in his painting—is located fifty kilometers to the southeast. Dürer is known to have visited Lake Garda. He produced a watercolor of Arco, a town five kilometers north of the lakeshore. Like Frederic Church’s Heart of the Andes, or Albert Bierstadt’s Storm in the Rockies, Dürer’s view of Trento is a composite, transporting us from the banks of the Adige to Riva del Garda, within a single image. The effect is almost cinematic.

During my time at Yale, Al Held loaned me a paperback copy of Film Form; a collection of writings by Sergei Eisenstein edited by Jay Leyda. One of the essays unpacks the concept of montage by describing a Kabuki performance. As the actor walks in front of a painted landscape, the muslin backdrop fell to the stage, revealing another landscape. One after the other, scrims drop with each step. Each is a different vista. Before the player had trod the boards from one end to the other, the audience had experienced a journey.

The late William Bailey made a comment that has resonated with me down the years. To paraphrase his remark; the point is not to copy whatever one looks at, but to invent from observation. Bill could have been talking about Cézanne, but Dürer had done it first. If plein-air painters are looking for a founding father, he would be fit the bill.

—James Lancel McElhinney © 2023

Thanks for posting this - big sketchbook and Durer fan here. . .

Thanks for posting this - big sketchbook and Durer fan here. . .