The writer sat at his desk looking north toward Mount Greylock, whose looming bulk gave form to the imaginary Leviathan. Day after winter’s day, clouds sailed past the snow-covered crest of the mountain that seemed at times to shrink and rise, as if it were drawing a breath. A few miles north of Melville’s farmhouse, the forks of the Housatonic powered the mills that supplied paper to publishers, printers, and the author himself.

Many years ago I brought my life-drawing class from Skidmore College to the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts—sitting in the shadow of Greylock, twenty miles north of Melville’s Arrowhead. The original museum sits on a grassy rise, just west of the village. Adjoining the stately white building is a dark Brutalist pile, at the head of a circular driveway. We were met by print and drawing curator Rafael Fernandez (1927-1999), who had emigrated from Cuba during the revolution, and trained at the Art Institute of Chicago. Fernandez had also hosted groups from Yale, and was in touch with Bernard Chaet. When Fernandez learned that I had been Bernie’s teaching assistant, we were welcomed with open arms. He led us into a large white room in which sat a large refectory table, opposite a chest-high bank of flat files. He had laid out a selection of works on paper; A sheet of landscapes and animal studies by Albrecht Durer, a chalk drawing by Rubens, of Hercules Strangling the Nemean Lion, a study for L'âge d'or by Ingres, a male nude in graphite by Degas, a gold-point portrait of Arsène Alexandre by Alphonse Legros, and an etching from Picasso’s Vollard Suite. All these works rested in mats—sandwiches of acid-free paper boards, into which had been cut windows through which ghostly images were visible through thin sheets of tissue. We all were given white cotton gloves to wear, and cautioned against getting too close for our breath to harm the fragile surfaces. Fernandez explained each of the pieces, as he opened its mat and removed the tissue, to reveal the naked page. This was a new experience for my students, who exhibited the same kind of timidity when our first model stepped onto the stand and dropped her robe.

Viewing drawings and prints in same condition that their makers would have known them. Without glass barriers and gold-frame theatrics, it was a bit like spotting a film star in the supermarket, sans costume or makeup. Chicago art dealer Richard Gray opined to me that amongst serious art collectors, an appetite for drawings was seen as a mark of refinement.

As the detritus of creative practice, drawings are also portals through which an artist’s innermost thoughts might be disclosed to attentive connoisseurs. A few of the students were astonished that the five-hundred-year-old Durer drawing could look so new, which Fernandez explained was because the artist had used archival materials. Durer’s paper was made from cotton and linen rags that had been shredded, soaked, and pulped. This slurry was spread across a screen, allowing excess water to escape. When sheets are sufficiently dry to come out of their frames, they are pressed between absorbent wool felt blankets to release any water that remains. Paper continues to be made by hand in this way at St. Cuthbert’s Mill in Somerset, England, Moulin de Larroque in the Dordogne region of France, and Papeterie St.-Armand in Montréal, Quebec, and other artisanal paper-mills around the globe. The durability of rag paper comes from fiber strength, and its neutral pH factor. Papers made from wood pulp contain high levels of acidity, which over time cause darkening, brittleness, and disintegration. On the return trip to Saratoga Springs, many of my students declared that our visit with Rafael had been the most memorable part of the trip. Most were unaware that anyone could make an appointment at most museums, to study works in storage. All it took was knowing how to ask. The experience of viewing au naturel works on paper is entirely different from looking at the same works behind glass, hanging in frames on the wall.

In 1996 I attended the exhibition Picasso and Portraiture: Representation and Transformation, at the Museum of Modern Art. A couple of elderly curmudgeons that remined me of Billy Crystal and Carol Kane in Princess Bride staggered from one piece to another, with audio-guide-paddles pressed to their ears. Once when they drifted apart, the wife grabbed her husband by the sleeve of his jacket. Beckoning him in a loud voice, she said. “Come here, come here! Have a look at this one!” Shaking her off, the husband barked back. “Leave me alone. I’m watching this one now.”

It seemed that for him, perusing an original Picasso was no different than tuning into The Lawrence Welk Show. Few painters will thank you for suggesting that their canvases are just an old-fashioned-image-delivery systems, like movie screens or television sets. A measure of deference conditions our behaviour in relation to artworks on display—not unlike the fictional barrieer that divides the actors onstage from ticketholders in the house. Thespians seldom break character to berate someone who forgets to silence their cellphone, but it happens. Interacting with an unframed print, drawing, or sketchbook by a famous artist can feel like running into a film star at the supermarket. Spending time with artworks in this way can almost become conversational—like sharing intimate secrets sotto voce, or honeymoon pillow-talk.

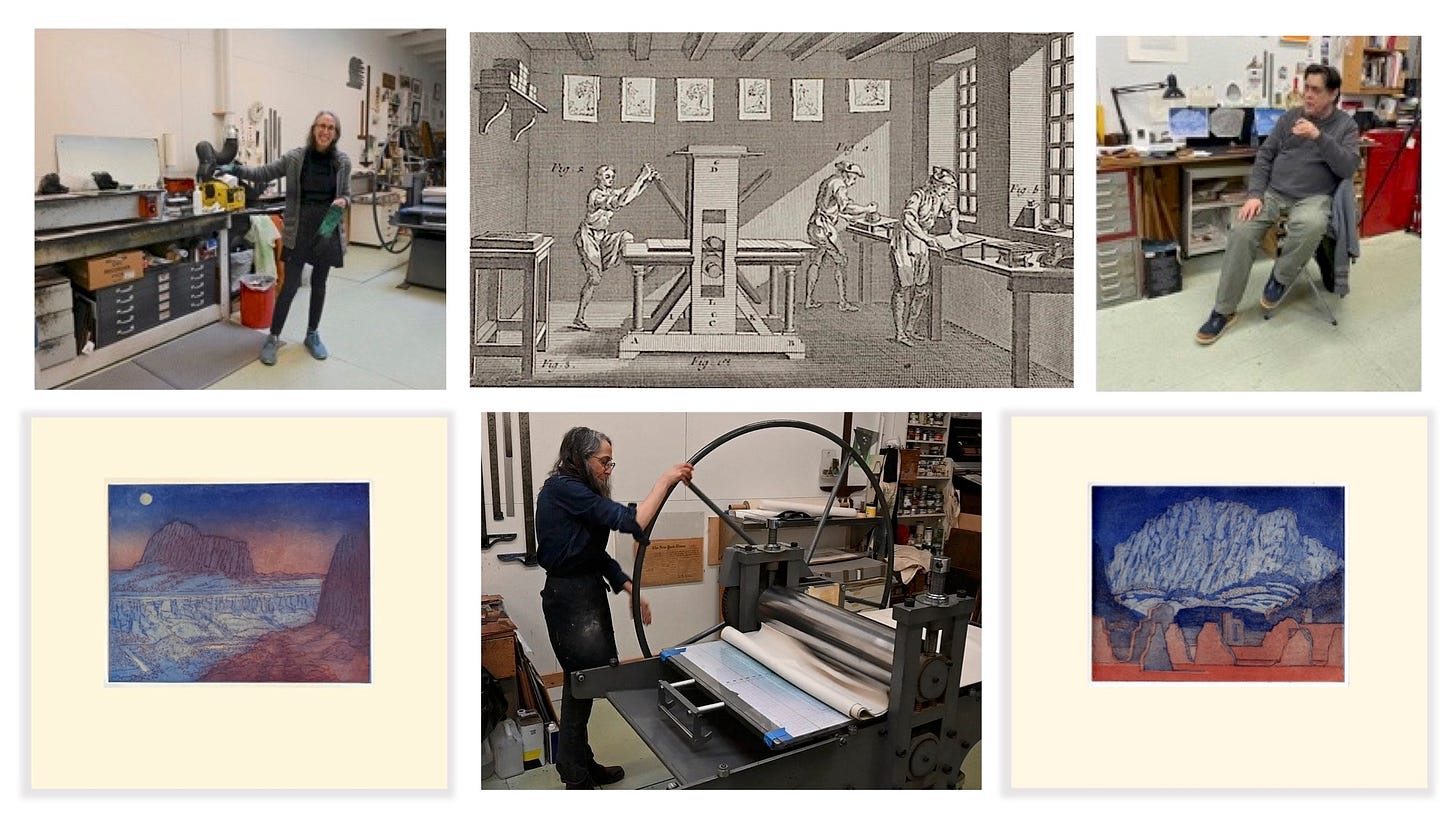

Collaborative printmaking embodies a conglomeration of creative desires. Its products carry something like the genetic code of a physical being. The soul of a print abides in all of its elements—from the ore that was mined, refined and rolled into copper plates, to the assorted other minerals that become pigments, chemicals, hand-tools, and press-machines. It lingers in traces of farm fields, where flax and cotton grow, and in their fibers; formed into artists’ paper by water, heat, and elbow grease. Rosin and varnish bear a distinct sillage of northern pines and tropical conifers. Artist and printers bring lifetimes of acquired skill, experience, and knowledge to their creative pas-de-deux. Blending art and alchemy reshapes materials into new iterations that exceed the sum of them all. In problem-solving, two heads are better than one. An unexpected benefit of working collaboratively is that outcomes can be unpredictable, which fuels uncertainty, sharpens the senses and focuses the mind. Failed experiments are chalked up to research, but sooner or later some happy ambush rewards us with results that solitude never allows.

An inky stain—pressed into a sheet of paper—might once have been seen as ephemera, but such distinctions are outmoded in the present digital age, in which a lobster has more in common with a cathedral than has either with binary codes. In order to appreciate artworks made by hand, one must look beyond images to uncover their backstories. Before you entomb a print under glass in a frame, touch the page. Run your finger across the printer’s blind-stamp. Feel the plate-mark. Smell the ink. Gaze deeply into the image, and strike up a conversation

—James Lancel McElhinney © 2024

THANKS FOR READING!

READ more about PRESSING MATTERS: Adventures in Printmaking: