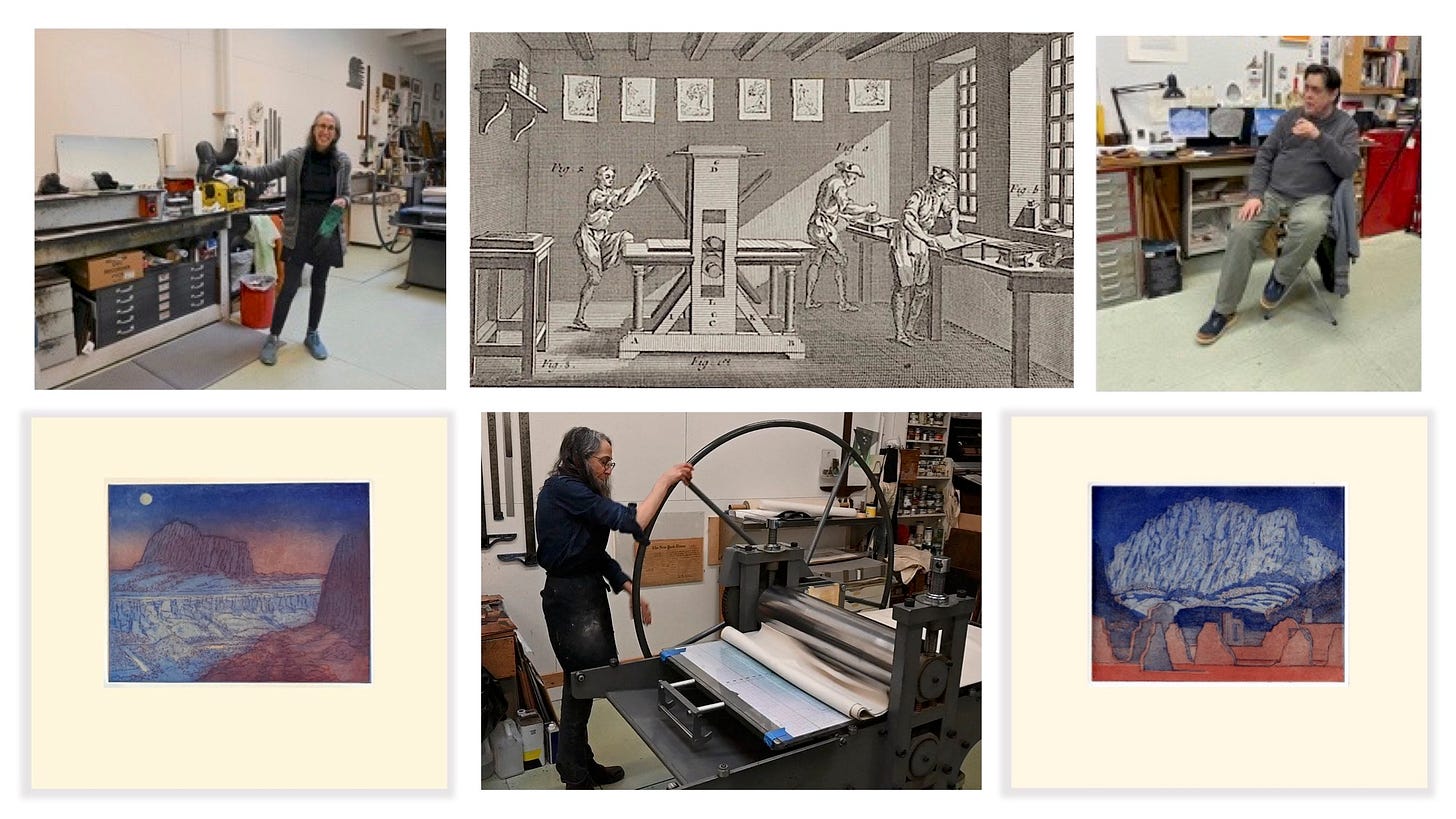

Rivers swelled. Storm drains flooded. The insistent patter of rain on the roof provided a steady backbeat to working with Cindi Ettinger in creating new etchings, just one month ago. We had first worked together in the late 180s, and more recently in 2018-19, when Cindi and I had experimented with blending digital printing with copperplate etching. These new prints are composites—amalgamated vistas drawn from the pages of my painting-journals. One of my personal gripes about much of contemporary landscape painting is its dependence on photo-conditioned imagery, because optical verisimilitude is usually achieved at the expense of more poetic attributes. Frederic Church had learned the limits of literal depiction from his Niagara. In Heart of the Andes, he brings us instead to an imaginary place, composed of multiple locations the artist had visited on his travels through South America.

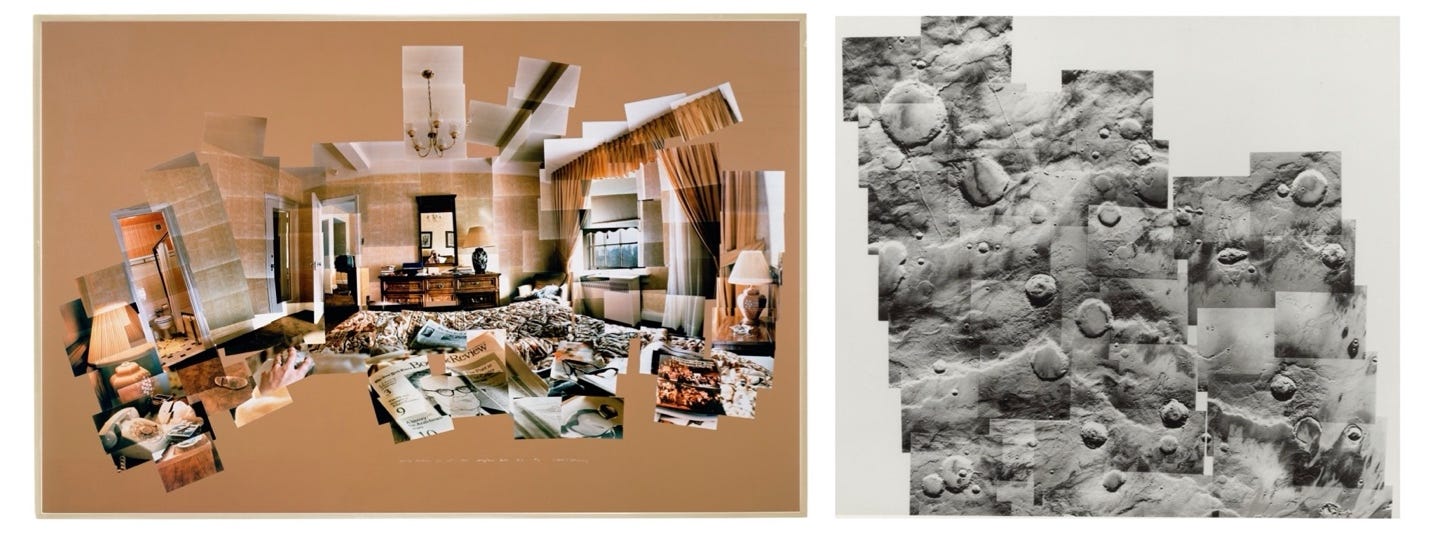

David Hockney and others have observed that human visual experience differs greatly from photography. Forty years ago, he created a series of photographic collages that resembled lunar snapshots beamed back to NASA. Critics compared them to Cubism, but my take on them is that Hockney was deconstructing how people actually look at things. Cinema, and especially animation, create time-based experiences that parallel what might happen to someone in real time. We got a surprise one evening, when our cat joined us in watching a video of Les Chats de Paris. Maeve stayed with it for twenty minutes but, like most felines, her patience had its limits. While she pays no attention to live-action videos, flat-shape animation was something she could read. Sergei Eisenstein’s use of cinematic montage, and Ken Burns’s trademark panning-shots of static images are some of the ways that filmmakers meet their audiences halfway.

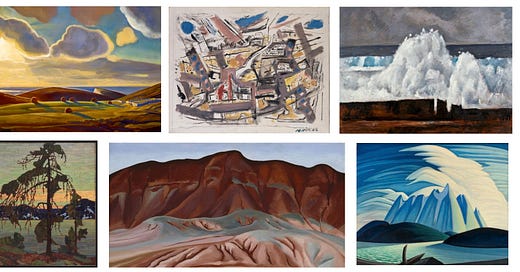

My longstanding interest in expeditionary art is rooted in understanding that it was created not to celebrate personal brilliance, but to increase useful knowledge. For example, many of the topographical views produced by explorers, military officers, and landscapists such as Paul Sandby, exhibit more refinement and imagination than much of the photo-mimicry of so-called realist painters today. While the camera gained acceptance as a legitimate tool for making art, tourism was on the rise. Anyone who could afford a Kodak Brownie box-camera collected snapshots of scenic destinations and tipped them into albums. While some photographers at the time produced stunning works of great merit, painters sought to capture their experiences in more inventive ways. John Marin, Marsden Hartley, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Rockwell Kent set up their easels on the rocky Maine coast, in New Mexico’s high desert, and along the Arctic margins of Labrador. The Canadian Group of Seven is lesser known in the United States. Its members paddled the Great Lakes, and trekked beyond their littoral zones, to paint wild forests, mountains, marshes and ponds. They were more intrigued by the prospect of capturing a sense of being somewhere, rather than just reproducing how a place looked.

In this way, they followed in the footsteps of Hudson River School painters, for whom optical mimesis could never ascend to art; a sentiment expressed by Edgar Allan Poe, whose death followed Thomas Cole by one year.

“Were I called on to define, very briefly, the term Art, I should call it 'the reproduction of what the Senses perceive in Nature through the veil of the soul.' The mere imitation, however accurate, of what is in Nature, entitles no man to the sacred name of Artist.”

Hercules Segers is an artist who has intrigued me for years. I became reacquainted with his work during a visit to the Rijksmuseum ten years ago. Segers’s work was the subject of a sweeping retrospective that had recently opened, and would travel to The Met in six months. While one might encounter a solitary print or a painting here or there; finding dozens of pieces gathered together in one venue was astounding. Working on an intimate scale, Segers was an artist who was well ahead of his time. His experimental printmaking techniques presaged the use of now-familiar practices, such as Chine-collé and monoprinting. Segers was a flatlander, whose dreamlike geologies and mountainous vistas foretold the surrealist frottages of Max Ernst. For sale in the Rijksmuseum bookshop was a limited edition of loose-bound facsimile reproductions of Segers’s etchings, accompanied by a descriptive essay in an illustrated chapbook. It was no accident that fate had thrown it in my path at just that moment. A few days prior to our arrival in Amsterdam, I had whiled away an afternoon in a treasure-trove of artist’s books by Sophie Calle, Dieter Roth, Candida Hofer, and others, in the back room of Buchhandlung Walther Koenig, Berlin.

On view at the same time at Rijksmuseum was as exhibition of zoological watercolors by Franz Post (1612-1680), who with fellow artist Albert Eckhout had been employed by Prince John Maurits of Nassau-Siegen in 1641, to paint the landscape, flora, and fauna of Dutch Brazil. As Kathie and I wandered through the show, it suddenly all made sense. Post had looked for facts through the veil of art, while Segers looked for beauty beyond the facts. Post’s paintings of anteaters, and Eckhout’s portraits of cannibals had been translated into prints by technicians, whereas Hercules Segers sidestepped the middle-men by working his own press. My own trajectory moving forward now was no longer a mystery.

—James Lancel McElhinney © 2024

CLICK the image below to read about more printmaking experiences on SUBSTACK