Times have changed, or have they? Art is today being created, distributed, and consumed in new ways—same as always. I wondered if the recent purge of confederate monuments was perhaps not just pushback against sentimentalist racism, but an assault against Western culture in general. Gilded Age statuary embodied conventional late 19th-century taste, and thus stood at odds with a nascent avant-garde modernism that conflated free expression with progressive values—a concept that was weaponized by the U.S. Information Agency as Cold War propaganda. Classical canons of beauty were decried in the last century, as hindrances to free expression, social reform, and progress. The western artistic tradition has more recently been disparaged as materialistic, colonialist, and racist. 20th century modernists imagined that dabbling in primitivism and non-western styles was a get-out-of-jail-free card—an escape from Eurocentric academism. Gauguin blended his taste for Japonisme with Polynesian subjects. Picasso purloined tropes from African masks. Kandinsky and Münter flirted with folk-art, but their art failed to become non-western.

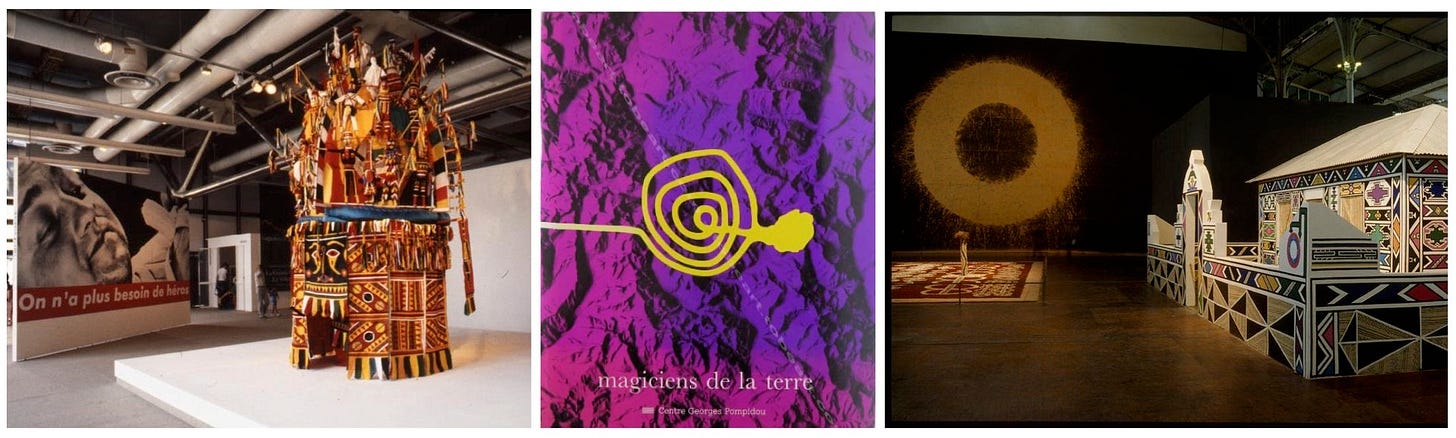

The 1989 exhibition Les Magiciens de la Terre at Centre Georges Pompidou attempted to foreground neglected artistic traditions by pairing contemporary artists such as Anselm Kiefer, Francesco Clemente, John Baldessari, and Richard Long—paired with Australian Aboriginal art, a Haitian Voudou shrine, Tibetan sand-painting, et cetera. Response to the Pompidou show echoed MoMA’s 1984 Primitivism exhibition being chastised for using tribal objects as “. . . footnotes or addenda to the Modernist avant-garde.” In other words, going native was just another of colonialism.

Kehinde Wiley’s Rumors of War depicts an African-American equestrian, astride a restless steed, whose raised right front hoof symbolizes that the rider was wounded in battle. Kathie and I saw the statue in September, 2019; shortly after its unveiling in Times Square—two months before its installation at Richmond’s Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, located on Arthur Ashe Boulevard beside The Virginia Museum of Culture and History—also known as Battle Abbey—and the headquarters of the United Daughters of the Confederacy. Rumor of War was a rebuke to the concatenation of Beaux-arts tributes to confederate heroes on nearby Monument Avenue, but it was not the first to do so. A storm of protest had erupted when the City of Richmond approved a plan in 1995, to install a monument to tennis star Arthur Ashe on Monument Avenue. Confederate memorialists regarded Paul di Pasquale’s sculpture as a cultural gatecrasher, while the African-American community was loath for its native son to rub shoulders with former oppressors. Ashe had approved di Pasquale’s design, if not its final location.

Wiley’s black horseman portrays no one in particular, unlike the wedding-cake statuary that once stood on Monument Avenue. With its hurricane windsock tail, Wiley’s raging steed is identical to the J.E.B. Stuart’s horse in the monument that was removed from the crossing of Franklin and Lombardy streets on July 7, 2020. The statue may have disappeared, but Stuart Circle still lingers on street maps. It seems that names offend less than images. Perhaps Stuart was given a pass because it bears other associations—such as a bygone royal family, the late African-American sportscaster Stuart Scott, or the actor Stuart Whitman, who often portrayed soldiers and cowboys. I knew a beautiful woman in Richmond whose given name was Stuart. Cloaked in such ambiguity, the Stuart name was allowed to remain—at least for now.

It also seemed that something about Virginia is deeply allergic to change. When Richmond hosted one of the Bush-Clinton presidential debates in 1992, it was dubbed a “hotbed of social rest.” I recall sipping a glass of rare whiskey and smoking a fine cigar, with the grandson of John Tyler, on the porch of the president’s hunting-lodge. We sat on a bluff overlooking the James River, watching bald eagles snatch Rockfish from the talons of ospreys. My host traced the ownership of his family’s land back to to Opechancanough’s Rebellion of 1622, and before. As a descendant of Pocahontas, and thus Powhatan, Mr. Tyler’s roots in this place ran deeper than Jamestown settlers. The late historian John Keegan declared Virginia the most English of all U.S. states—not only because of its pastoral landscape and tidewater aristocracy, but by the value it places on history. Indigenous communities displaced by colonists are remembered in hydronyms such as Chickahominy, Mattaponi, and Appomattox, while toponyms such as Chester, Gloucester, Montrose, and Midlothian recall place-names from the British Isles.

Excepting the James and Elizabeth rivers, most Virginia waterways bear Algonkian names—such as Pamunkey, Shenandoah, Rappahannock, and Potomac. These represent The Old Dominion’s ancient provenance, while settlement-names such as Richmond, Hampton, Norfolk, and Surry reflect Cavalier suzerainty over conquered lands.

Enslaved ethnic Africans endured centuries of forced labor, bearing their masters’ surnames. An 1806 law required persons freed from bondage to leave Virginia with a year, or risk enslavement again. This ethnic cleansing shielded white supremacist eyes from the vexing sight of black folks at liberty. While immigrants from the margins of Europe disguised their ethnic origins to hasten assimilation, Alex Haley inspired his fellow African-Americans to reclaim the lost names of their enslaved forebears. Playwright Arthur Miller’s father was a Polish immigrant, whose hometown of Radomyśl Wielki was flattened during World War II. Most of its Jews were murdered by Nazis, before the Red Army wiped out the rest. In final act of The Crucible, a defiant John Proctor stands on the gallows and asks,

“How may I live without my name? I have given you my soul. Leave me my name!”

(End of Part 1)

—James Lancel McElhinney © 2025

NB: All images herein are reproduced under Fair Use for crucial and educational purposes